Illegitimate Authority: Dealing With the Difficulties of Our Time

by Noam Chomsky, modified by C.J. Polychroniou

Haymarket Books, 2023; x + 330 pp.

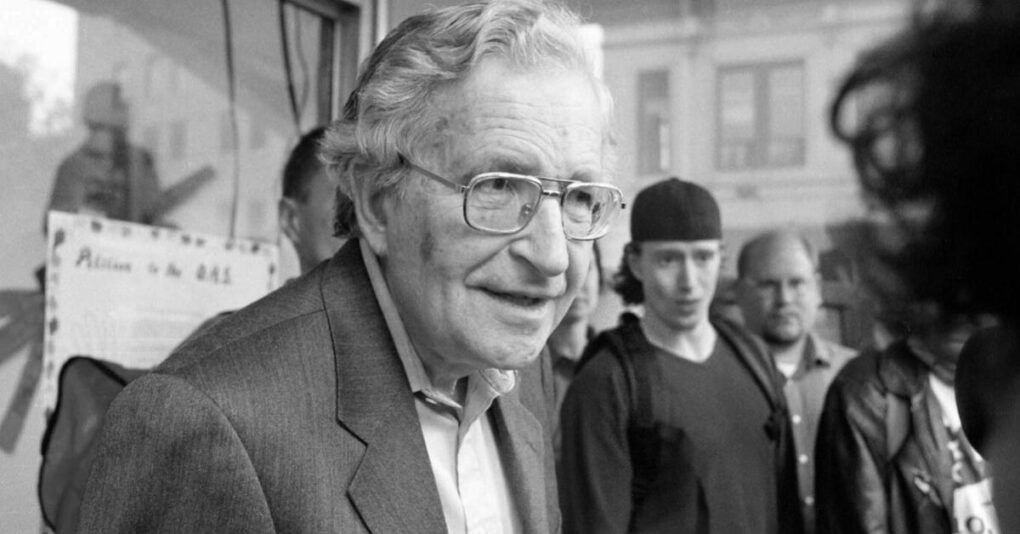

Noam Chomsky is widely appreciated for his contributions to linguistics and to the philosophy of mind, however he is a “public intellectual” too, and it is in the general public arena that opinion about him is divided. Illegitimate Authority is a collection of thirty-four interviews of him by C.J. Polychroniou, the book’s editor, and the economist Robert Pollin, and reading it makes clear why individuals respond strongly to Chomsky’s viewpoints. He consults with supreme self-esteem, and if you disagree with him, you are likely to turn away madly. I typically felt like doing this while reading the book, however nonetheless what he says is frequently insightful. In quick, Chomsky is better on foreign policy than on the economy.

He rightly deplores crony capitalism, the use by industry of state-granted advantages to acquire wealth. By no methods, though, does he call for the state to get out of the economy. To the contrary, he argues that the free enterprise might not function at all without an interventionist state:

The masters of humanity have actually always understood that free-market capitalism would destroy them and the societies they owned. Accordingly, they have constantly called for a powerful state to secure them from the devastations of the market, leaving the less lucky exposed. That has actually been dramatically plain in the course of the “bailout economy” of the past forty years of class war, masked under “free enterprise” rhetoric.

If you ask why he thinks that the free enterprise must be unsteady, a surprising reality emerges. He provides no defense of this view at all. If challenged, Chomsky would doubtless cite lots of “progressive” economists who concur with him, in addition to an abundance of truths and figures; but there would be no extensive argument that capitalism should break down. This approach remains in marked contrast to that of his work in linguistics, which is based on theoretical factors to consider that are plainly set forward. In questions of public affairs, Chomsky profits by attempting to overwhelm people with facts, or expected facts, drawing on his large reading and capacious memory.

He knows Ludwig von Mises, however he offers no action to Mises’s presentation that the free enterprise is the only workable system of social cooperation. Incredibly, he concerns Mises as the daddy of “neoliberalism,” Chomsky’s name for crony industrialism. He calls Mises “the revered creator of the neoliberal motion that has actually reigned for the past forty years.” We find out that the “core functions of the ruling state capitalist institutions have actually been intensified by the rot spreading from interwar Vienna, adopting the term ‘neoliberalism’ in the worldwide Walter Lippmann seminar in Paris in 1938, then in the Mont Pelerin society.” He provides the standard distortion of Mises’s comments on Italian fascism in Liberalism (1927 ); for an account of what Mises meant, see my “Mises and Fascism.”

As I discussed earlier, though, Chomsky is better on diplomacy. His greatest point is his undaunted opposition to war. He recognizes the function of what Murray Rothbard called “court intellectuals” in fomenting the war spirit:

A few years later, in 1916, Woodrow Wilson was chosen president with the motto “Peace without Success.” That was quickly transmuted to Victory without Peace. A flood of war myths quickly turned a pacifist population to one taken in with hatred for all things German. The propaganda initially emanated from the British Ministry of Details … American intellectuals of the liberal [John] Dewey circle lapped it up enthusiastically, stating themselves to be the leaders of the campaign to liberate the world. For the very first time in history, they soberly discussed, war was not started by military or political elites, but by the thoughtful intellectuals– them– who had thoroughly studied the scenario and, after careful consideration, rationally identified the ideal course of action: to enter the war, to bring liberty and freedom to the world, and to end the Hun atrocities prepared by the British Ministry of Information.

In the present atomic age, when wars have the potential to ruin life in the world, it has become a lot more essential than at the time of the world wars, with all their dreadful horrors, to seek peace. Chomsky can not be considered a partisan of Vladimir Putin, whom he considers a war criminal, but he firmly turns down the policy of huge arms shipments to Ukraine by the United States. This policy has led to a proxy war in between Russia and America that may intensify into nuclear war, and to avoid this supreme disaster, we should seek compromise, Chomsky asserts.

He keeps in mind that Graham Allison, an outstanding authority who strongly opposes Putin, recognizes this need:

A diplomatic settlement must offer Putin some kind of escape hatch– what is now disdainfully called an “off-ramp” or “appeasement” by those who choose to extend the war. That much is comprehended even by the most devoted Russia-haters, at least those who can captivate some thought in their minds beyond punishing the reviled opponent. One popular example is the recognized diplomacy Graham Allison of Harvard University’s Kennedy School of Government, who also has long direct experience in military affairs … few can question that Putin is a “demon” radically unlike any United States leader, who at worst just makes mistakes, in [Allison’s] view. Yet even Allison argues that we must contain our righteous anger and bring the war to a quick end by diplomatic methods. The reason is that if the mad devil “is required to pick in between losing and escalating the level of violence and damage, then, if he’s a rational star, he’s going to choose the latter”– and we may all be dead, not simply Ukrainians.

Can anything be done by those of us outside the federal government to promote peace? Chomsky offers a helpful tip, and here he again echoes Rothbard. He keeps in mind that federal government eventually rests on public opinion; if this turns against a war, the federal government might feel alluring pressure to alter its course:

In among the first operate in what is now called government, 350 years ago, his “First Principles of Government,” David Hume composed that

… We shall find that, as Force is constantly on the side of the governed, the governors have nothing to support them however opinion. It is, for that reason, on viewpoint only that federal government is established; and this maxim reaches the most despotic and most military governments, as well as the most totally free and most popular.”

If this is right, a figured out project for peace has a great chance of achieving its goals– if it wins over the general public.

Those who check out Illegitimate Authority will need to sort out the great ideas from the nonsense in the book. There is lots of both.