Wherever blame for the war may lie, for the tremendous majority of Americans in 1914 it was simply another of the European horrors from which our policy of neutrality, set forth by the Establishing Dads of the Republic, had kept us free. Pašić, Sazonov, Conrad, Poincaré, Moltke, Edward Grey, and the rest– these were the males our Fathers had alerted us versus. No imaginable result of the war might threaten an intrusion of our vast and strong continental base. We must thank a merciful Providence, which offered us this blessed land and impregnable fortress, that America, at least, would not be drawn into the ridiculous butchery of the Vintage. That was unthinkable.

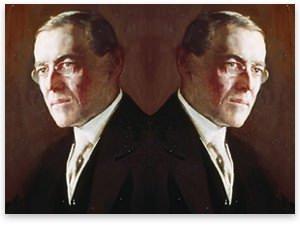

However, in 1914 the president of the United States was Thomas Woodrow Wilson.

The term most regularly applied to Woodrow Wilson nowadays is “idealist.” In contrast, the expression “power-hungry” is seldom utilized. Yet a scholar not hostile to him has written of Wilson that “he liked, longed for, and in a sense glorified power.” Musing on the character of the US federal government while he was still an academic, Wilson composed: “I can not think of power as a thing unfavorable and not positive.” Even before he entered politics, he was fascinated by the power of the presidency and how it might be enhanced by meddling in foreign affairs and dominating abroad areas. The war with Spain and the American acquisition of colonies in the Caribbean and throughout the Pacific were invited by Wilson as efficient of salutary modifications in our federal system. “The plunge into global politics and into the administration of distant dependences” had already led to “the significantly increased power and opportunity for useful statesmanship provided the President.”

When foreign affairs play a feature in the politics and policy of a country, its Executive needs to of need be its guide: should utter every preliminary judgment, take every primary step of action, provide the information upon which it is to act, suggest and in big procedure control its conduct. The President of the United States is now [in 1900], as of course, at the front of affairs … There is no difficulty now about getting the President’s speeches printed and checked out, every word … The federal government of dependencies must be largely in his hands. Fascinating things may come of this singular change.

Wilson eagerly anticipated an enduring “new leadership of the Executive,” with even the heads of Cabinet departments working out “a brand-new impact upon the action of Congress.”

In big part Wilson’s track record as an idealist is traceable to his ceaselessly professed love of peace. Yet as soon as he ended up being president, prior to leading the nation into the First World War, his actions in Latin America were anything but pacific. Even Arthur S. Link (whom Walter Karp described as the keeper of the Wilsonian flame) wrote, of Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean: “the years from 1913 to 1921 [Wilson’s years in office] witnessed intervention by the State Department and the navy on a scale that had never ever before been pondered, even by such alleged imperialists as Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft.” The protectorate extended over Nicaragua, the military occupation of the Dominican Republic, the invasion and subjugation of Haiti (which cost the lives of some 2,000 Haitians) were landmarks of Wilson’s policy. All was covered in the haze of his patented rhetoric of freedom, democracy, and the rights of small nations. The Pan-American Pact which Wilson proposed to our southern next-door neighbors guaranteed the “territorial stability and political independence” of all the signatories. Thinking about Wilson’s consistent interference in the affairs of Mexico and other Latin states, this was hypocrisy in the grand design.

The most outright example of Wilson’s bellicose interventionism prior to the European war was in Mexico. Here his attempt to control the course of a civil war result in the fiascoes of Tampico and Vera Cruz.

In April, 1914, a group of American sailors landed their ship in Tampico without authorization of the authorities and were jailed. As quickly as the Mexican commander become aware of the occurrence, he had the Americans launched and sent out an individual apology. That would have been completion of the affair “had not the Washington administration been looking for an excuse to provoke a fight,” in order to benefit the side Wilson preferred in the civil war. The American admiral in charge required from the Mexicans a 21-gun salute to the American flag; Washington backed him up, issuing a demand demanding the salute, on discomfort of alarming consequences. Naval units were ordered to take Vera Cruz. The Mexicans resisted, 126 Mexicans were killed, close to 200 injured (according to the United States figures), and, on the American side, 19 were killed and 71 injured. In Washington, strategies were being made for a major war versus Mexico, where in the meantime both sides in the civil war denounced Yanqui aggression. Lastly, mediation was accepted; in the end, Wilson lost his bid to control Mexican politics.

2 weeks before the assassination of the archduke, Wilson delivered an address on Flag Day. His remarks did not bode well for American abstention in the coming war. Asking what the flag would mean in the future, Wilson replied: “for the simply usage of undeniable national power … for self-possession, for dignity, for the assertion of the right of one nation to serve the other countries of the world.” As president, he would “assert the rights of humanity wherever this flag is unfurled.”

Wilson’s modify ego, a significant figure in bringing the United States into the European War, was Edward Mandell Home. House, who bore the honorific title of “Colonel,” was considered as something of a “Male of Mystery” by his contemporaries. Never ever elected to public office, he however ended up being the second most powerful man in the nation in domestic and particularly foreign affairs till virtually the end of Wilson’s administration. House began as a business owner in Texas, increased to management in the Democratic politics of that state, and then on the national phase. In 1911, he attached himself to Wilson, then Guv of New Jersey and an ambitious candidate for president. The two became the closest of collaborators, Wilson going so far regarding make the strange public declaration that: “Mr. House is my second character. He is my independent self. His ideas and mine are one.”

Light is cast on the mindset of this “male of mystery” by a futuristic political unique House released in 1912, Philip Dru: Administrator. It is a work that contains odd anticipations of the function the Colonel would help Wilson play. In this strange production, the title hero leads a crusade to topple the reactionary and overbearing money-power that rules the United States. Dru is a veritable messiah-figure: “He comes panoplied in justice and with the light of factor in his eyes. He comes as the supporter of equal opportunity and he features the power to impose his will.” Assembling a fantastic army, Dru confronts the massed forces of evil in a titanic battle (near to Buffalo, New York): “human liberty has never more surely hung upon the result of any dispute than it does upon this.” Naturally, Dru victories, and becomes “the Administrator of the Republic,” assuming “the powers of a totalitarian.” So absolutely pure is his cause that any attempt to “foster” the reactionary policies of the previous federal government “would be considered seditious and would be penalized by death.” Besides fashioning a new Constitution for the United States and developing a well-being state, Dru joins with leaders of the other excellent powers to remake the world order, bringing liberty, peace, and justice to all mankind. A strange production, suggestive of a very strange guy, the 2nd essential man in the country.

Wilson made use of Home as his personal confidant, consultant, and emissary, bypassing his own designated and congressionally inspected officials. It was somewhat comparable to the position that Harry Hopkins would fill for Franklin Roosevelt some twenty years later.

When the war broke out, Wilson implored his fellow citizens to stay neutral even in word and idea. This was rather disingenuous, considering that his whole administration, except for the bad baffled secretary of state, William Jennings Bryan, was pro-Allied from the start. The president and the majority of his chief subordinates were dyed-in-the-wool Anglophiles. Love of England and all things English was an intrinsic part of their sense of identity. With England threatened, even the chief justice of the United States Supreme Court, Edward D. White, voiced the impulse to leave for Canada to offer for the British armed forces. By September 1914, the British ambassador in Washington, Cecil Spring-Rice, was able to assure Edward Grey, that Wilson had an “understanding heart” for England’s problems and challenging position.

This deep-rooted predisposition of the American political class and social elite was galvanized by British propaganda. On August 5, 1914, the Royal Navy cut the cables linking the United States and Germany. Now news for America needed to be funneled through London, where the censors shaped and trimmed reports for the benefit of their government. Ultimately, the British propaganda device in the First World War became the best the world had seen to that time; later it was a design for the Nazi Propaganda Minster Josef Goebbels. Philip Knightley noted:

British efforts to bring the United States into the war on the Allied side permeated every phase of American life … It was one of the major propaganda efforts of history, and it was carried out so well and so privately that little about it emerged till the eve of the 2nd World War, and the complete story is yet to be informed.

Already in the very first weeks of the war, stories were spread out of the ghastly “atrocities” the Germans were devoting in Belgium. However the Hun, in the view of American fans of England’s cause, was to show his most hideous face at sea.

Excerpted from Terrific Wars and Fantastic Leaders: A Libertarian Rebuttal( 2010 ).