In the wake of the American Civil War, one’s status as a veteran could bring considerable social and economic advantages. Certainly, the Grand Army of the Republic would become a very influential interest group and helped sustain the early development of an American well-being state for veterans. “Do it for the veterans” became a common plea delivered to politicians of the time.

Yet, it was likewise the case that actively preventing military service– what we might call today “draft dodging”– throughout the war was not an obstacle to appeal. Mark Twain was an authentic “wrongdoer” who fled his home state in order to prevent military service. Other renowned authors of the period– particularly Henry Adams and William Dean Howells– easily managed to get jobs outside the United States during the duration of the war. Novelist Henry James claimed to have actually suffered an unclear nonspecific injury that kept him out of military service.

Additionally, two later United States presidents prevented service throughout the war, particularly Chester A. Arthur and Grover Cleveland. Their political careers obviously didn’t suffer much from their absence of military experience.

Possibly the absence of basic disdain for those who never ever used a federal uniform can be discovered in the reality that preventing enlistment was not exactly unusual throughout the war. That’s not to state the regime was incapable of finding hundreds of thousands of ready recruits and volunteers. Many happily signed up.

Yet not all of America’s boys bought into the propaganda.

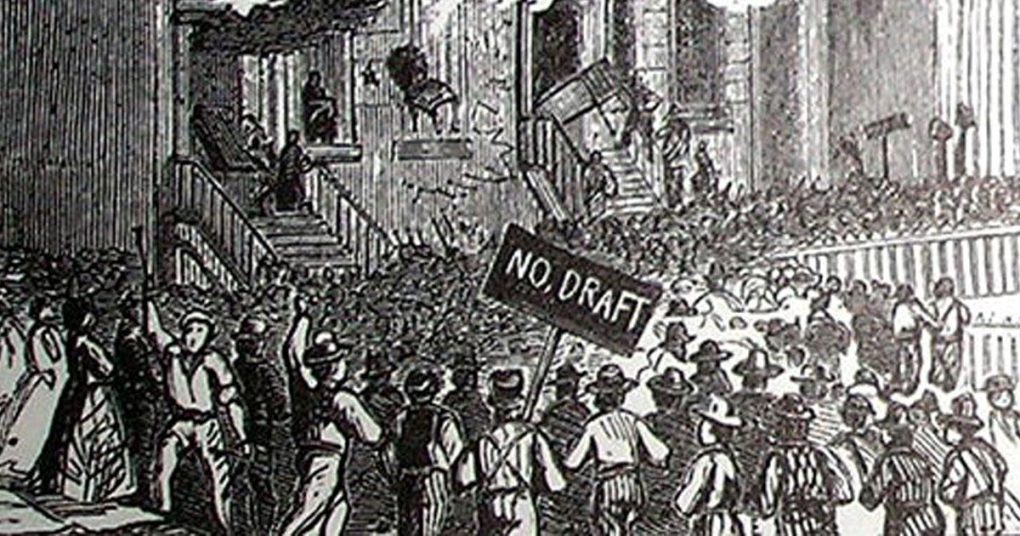

Riots and Attacks on Draft Agents

The very first national draft in the Union began with the militia law of July 1862, which allowed for a draft if states did not satisfy their quotas of three-year volunteers. A draftee might acquire a “commutation” with the payment of $300, or employ a replacement at the exact same rate.

Riots versus these impositions soon flared up.

The New York draft riot is the most typically mentioned example– because it was so fatal. But scattered draft riots happened in other cities and towns throughout the US.

Numerous draft riots were highly targeted, looking for to prevent draft representatives from carrying out their tasks. In Boston in 1863, for example, working-class Irish Americans– a number of them females who feared economic ruin if their wage-earning guys were sent to war– attacked the local draft representatives.

Midwesterners remained in lots of cases likewise opposed to conscription.

One example was the riot of November 1862 in Ozaukee County, Wisconsin. The regional paper– a paper unsympathetic to the rioters– explains how the local draft commissioner and district lawyer was attacked as he tried to conduct a draft in the county: Mr. Pors then talked to [the crowd of men and women] in a moderate way

, requesting them to stand back a little and they might all see that the draft was performed effectively. At this was a rush forward. Many of them were armed with clubs, lots of had substantial stones in their hands, and others had various carries out. The first thing done was to demolish the draft box with a club, and they took hold of Mr. Pors, and rather stomped upon him, the ladies vieing [sic] with the males in the brutish attack. The crowd then proceeded to toss Pors down the court house actions. He got away for his life as rioters hurled heavy stones at his head. The crowd then relied on the court house and destroyed the registration lists. In Wisconsin, as elsewhere, numerous likewise resisted more passively. One historian recounts how “[ m] en possessed of robust health all of a sudden found some horrible disorder and had to look for treatmentin a different environment. Canada at the same time became a Capital for such invalids.”Numerous city governments offered money perks in exchange for enlistment. It was hoped this would provide enough employees so that making use of a draft might be avoided

completely. It was understood an active draft would prompt rage from numerous voters. The payment of bounties ended up being a considerable cost for numerous state and community federal governments in the face of public resistance to enlistment. Undoubtedly, as the war continued,”bounties and unique offerings from the city governments “were progressively essential to stimulate recruiting. The Chicago area, for example, experienced rising resistance into 1863 and beyond. The preliminary interest for war had actually dissipated and Chicagoans started to feel they had actually already provided enough to the war effort.

As Bessie Louis Pierce noted in her history of Chicago,”Reports that Chicago soldiers in the field were refusing to follow orders and had suffered arrest were added evidence that numerous were ending up being weary of the war. “The local media in Chicago started to oppose continuous efforts at recruitment too. The Chicago Tribune came out versus the draft in 1864, and Pierce writes: Chicago faced the draft when Lincoln once again required

troops [in December 1864] For the next few weeks defiance was the managing feeling. 3 yearsprior to Chicagoans had actually pled the advantage of fighting; now mass meetings opposed what was thought about an unfair evaluation upon her guy power … as numerous as 3 or 4 hundred guys accountable to conscription were reported as leaving everyday for Canada or “for parts unknown”; aliens, especially the Irish, excitedly looked for papers which guaranteed flexibility from call. The undercurrent of resistance took its toll on draft efficiency. Timothy Perri, for example, has actually revealed that 20 percent of men called by the draft just never ever showed up. The Economics of Substitutes Whenever Civil War draft policies are discussed, one inevitably becomes aware of substitutes. This was the policy under

which a draftee might pay another guy to enlist instead. The main cost of an alternative was$ 300, which lots of have explained was equal to a year’s incomes in manufacturing.

Not remarkably, the replacement policy is thus frequently slammed for not being sufficiently egalitarian, and many have competed just the wealthy could manage this choice. In practice, however, the capability to hire an alternative was not unattainable for the middle class. Pierce points out that “[http://www.appstate.edu/~perritj/DraftHis”>. m] utual protective associations were arranged to buy freedom for draftees.”These associations operated as a kind of”draft insurance coverage”cost effective to common, middle-class families. Perri keeps in mind fees(i.e., premiums)for draft insurance coverage” ranged from $10 to$50 in Ohio … Late in the war, companies in Illinois and Indiana offered explicit draft insurance.

Draftees who bought insurance had actually replacements employed for them.”Additionally, the substitute technique gave families choices they would not otherwise have actually had. That is, extended families could pool their resources to replace one child for another if the preparing of a particular high-earning child could result in monetary destroy for the family. The competitors for substitutes likewise drove up reliable salaries for military service, that made military service less economically burdensome, if nevertheless still basically obligatory. Pierce notes,” As the war wore on costs for these alternatives followed the market … By summer, 1864, three-year guys could demand from $550 to$650, and by spring of the next year $900 was sometimes asked.”This likely showed a basic decline of determination to get amongst boys, meaning possible alternatives might demand greater and greater rewards for an unpopular job. Local governments nevertheless felt the political pressure to offer leaves from the draft, and some jurisdictions allocated funds “to purchase substitutes for married men.”All of this, of course, proved to make business of hiring soldiers more intricate and more pricey to the regime in regards to time and resources. While likewise expensive to normal

individuals, the substitute policy did nonetheless supply versatility that would not otherwise have actually been available. Eventually, though, this patchwork of bounties, commutations, and alternatives was necessary to prevent even more enthusiastic opposition. After all, by the mid-nineteenth century, Americans had been relocating the opposite direction of a national draft: voluntary militias

had become the rule in the North, and the United States in the 1840s had actually fought a war staffed just by volunteers. Hence, numerous Americans in the 1860s seen conscription with discouragement and an attitude of defiance to a degree that would end up being mostly unknown once again till the Vietnam War. Regrettably, nevertheless, the Civil War draft would prove to

contribute in stabilizing federal conscription. It prospered in this venture, and in the twentieth century commutations and replacements were disallowed. A nationwide “selective service”registration system was imposed. By the First World War– and for years afterward– America had actually ended up being willing to tolerate a much more exorbitant and widespread draft than had actually ever been implemented during the Civil War.