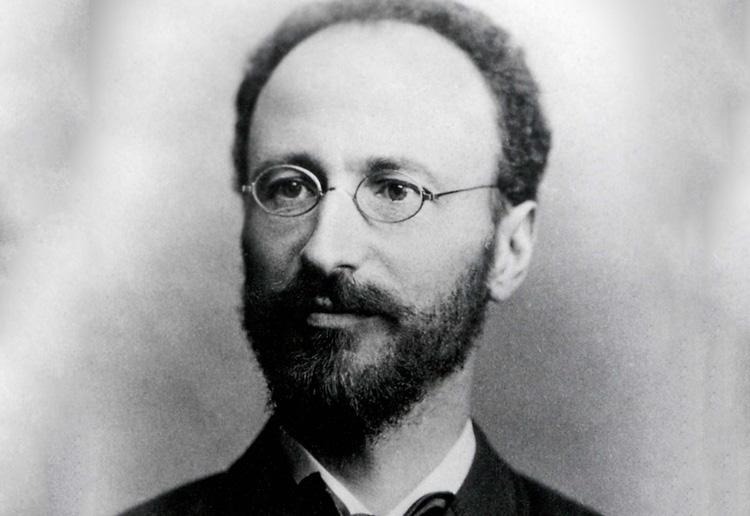

Austrian economic expert Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk is known among historians of economic idea for his powerful History and Review of Interest Theories( 1884 ). Before using his own explanation of the phenomenon of interest (in a second volume which appeared 5 years later on), Böhm-Bawerk first methodically classified and refuted all previous explanations.

In my own history of financial thought class, I assign several of Böhm-Bawerk’s critiques as reading for my trainees. I do this not so much since someone may hold the (incorrect) view in concern, however rather due to the fact that Böhm-Bawerk’s arguments are of great pedagogical value.

Simply put, the amateur can find out a good deal about economics by reading Böhm-Bawerk’s reviews.

In previous short articles I have discussed (what Böhm-Bawerk called) the “naïve efficiency theory” and also the “abstinence theory” of interest. In today post I wish to sum up Böhm-Bawerk’s review of the “exploitation theory.”

The Exploitation Theory of Interest

The exploitation theory could be equally well titled the socialist theory of interest, however Böhm-Bawerk chose the former name since of its greater accuracy. After discussing that lots of authors had advanced numerous versions of the exploitation theory, Böhm-Bawerk decided to concentrate on the specific exegesis of Rodbertus, because his was the clearest and most coherent variation.

Rodbertus’ explanation of interest is itself based on a labor theory of value, in which the worth of a commodity is identified by the amount of (overall) labor involved in its production. The reality that the capitalists take in products year after year, even though they may not carry out any work themselves, is only possible since the workers jointly are paid less than the full product of their labor. The real system by which this transfer is effected is the institution of personal property; the capitalists remain in a position to demand that employees send to their unjust wages since otherwise the employees will starve. In Rodbertus’ own words:

Given that there can be no income, other than as it is the outcome of labor, an excess of profits over labor costs depends upon two indispensable prerequisites. Initially, there can be no surplus proceeds unless the labor at least produces more than is needed for the continuation of the labor. For it is impossible for anyone to draw an earnings regularly [,] without himself doing any work [,] unless there is such a margin. Second, there can be no surplus profits, unless [organizations] exist which deny the workers of this margin in whole or in part, and divert it to others who do not work themselves. For the employees are, in the nature of things, in belongings of their product at the beginning … That this margin is wrested in whole or in part from the workers and is diverted to others, is the result of legalistic elements. Simply as law has from the beginning been in union with power, so in this circumstances this diversion happens only by the continued workout of compulsion. (Rodbertus priced quote in Böhm-Bawerk pp. 252– 53)

Böhm-Bawerk’s Review of Rodbertus

The very first objection Böhm-Bawerk raises is Rodbertus’ reliance on a labor theory of worth. It is simply not true that goods obtain their worth from the total labor used in their production. Böhm-Bawerk advances several arguments to show this, but the labor (or more generally, cost) theory of value has been exploded in other short articles and I will not invest more time on it here.

Böhm-Bawerk too follows this method. After demolishing the labor theory of worth upon which Rodbertus’ explanation of interest rests, Böhm-Bawerk composes,

In order not to draw unnecessary benefit from Rodbertus’s first mistake, I shall, for the staying pages of this examination, frame all my presuppositions in such a way as to get rid of completely all the effects of that mistake. I will [presume] that all goods are produced only by the cooperation of labor and free forces of nature … without the intervention of natural product resources having exchange value. (Böhm-Bawerk p. 263, italics initial).

Simply put, Böhm-Bawerk will now proceed to reveal that even if we limit ourselves to cases where labor is the only limited resource used in the production of a certain good, the exploitation theory is still malfunctioning.

Labor Is Paid Its “Full Value”!

Ironically, Böhm-Bawerk profits by yielding the socialist maxim: He too agrees that the employees should get paid the full item of their labor. Nevertheless, the exploitation theorists dedicate a grave mistake in the application of this principle:

The completely just proposal that the employee is to receive the whole worth of his product can be reasonably translated to suggest either that he is to get the complete present worth of his item now or that he is to get the whole future worth in the future. But Rodbertus and the socialists interpret it to indicate that the worker is to get the entire future worth of his product now. (Böhm-Bawerk pp. 263– 64, italics initial)

Once we acknowledge that present goods are better than future goods– that people would choose $1000 or a pizza pie today rather than $1000 or a pizza pie in fifty years– this obscurity in the exploitation teaching renders it completely incorrect. The explanation for Rodbertus’ “surplus earnings”– the fact that the capitalist gets more by offering the item to customers than the overall amount he paid to workers in producing it– is not exploitation, however rather that the workers were paid before the end product could be offered to customers. It is the time distinction that explains the interest income made by capitalists.

An Example

As constantly, Böhm-Bawerk shows his basic arguments with particular examples to assure the dissatisfied reader. He asks us to imagine a steam engine that needs 5 years of labor to produce, and has a last price of $5,500. Expect that one employee labors for five successive years to produce one such engine. Just how much is the employee due? The obvious response is $5,500, i.e., the full value of his item. However notification that the worker can just be paid this “complete” quantity if he is going to wait the full 5 years.

Now what if we have a more realistic situation, where the employee is paid in continuous annual installments? In particular, suppose the employee labors for simply one year, and then anticipates to be paid. Just how much is he due? Böhm-Bawerk responses, “The employee will get justice if he gets all that he has actually labored to produce approximately this point. If … he has up to this time produced a pile of unfinished ore … then he will be justly dealt with if he receives … the complete exchange value which this stack of material has, and naturally has now” (p. 264).

And now we must inquire further: What will be the precise dollar worth of this incomplete ore? A shallow analysis may show that, because the worker has actually produced (up until now) one-fifth of the labor going into the steam engine, then the employee ought to receive one-fifth of the exchange value of a steam engine, i.e. $1,100. Yet Böhm-Bawerk declares:

That is incorrect. One thousand one hundred dollars is one-fifth of the cost of a completed, present steam engine. But what the employee has produced up to this time is not one-fifth of a device that is already completed, but only one-fifth of a machine which will not be finished for another 4 years. And those are 2 different things. Not various by a sophistical splitting of spoken hairs, however in fact different as to the thing itself. The previous fifth has a value various from that of the latter 5th, just as definitely as a total present machine has a various value in terms of present appraisal from that of a machine that will not be offered for another 4 years. (pp. 264– 65)

Due to the fact that present items are more valuable than future products, it always follows that one-fifth of a machine-to-be-delivered-in-four-years deserves less than one-fifth of a present steam engine. For that reason, the worker can not perhaps be paid $1,100 for his first year of labor, if he insists on payment upfront (instead of waiting up until the engine is completed and sold). If we assume an interest rate of 5 percent, the employee will be paid roughly $1,000 for his very first year of labor.

Workers Can Always Choose to Lend Their Incomes at Interest

Böhm-Bawerk uses yet another argument to persuade the skeptic. If there is any doubt that the employee above is being treated relatively by being paid just the marked down value of his minimal item (i.e. $1,000) rather than the eventual present worth of his minimal product, Böhm-Bawerk mentions that the employee is certainly totally free to provide his salaries out at the prevailing interest rate of 5 percent each year. After four years, the employee will have $1,200 (overlooking compounding), and there is hence no basis to claim that the institutional structure in some way forces the employee to receive less than the full value of his contribution.

If the employee wants to wait till the item of his labor in fact accrues into a commercial product, then he will have the “full value” that even a socialist analysis would need. Nevertheless, if the worker is not happy to wait, and desires an advance in the kind of present products in exchange for his labor (that will not produce consumable items until the future), then he should be willing to pay the market premium on present goods.

Conclusion

Böhm-Bawerk’s refutation of the exploitation theory is important not simply as a review of an incorrect doctrine, but also as a lucid exposition of subjective worth theory. Even the professional economist would most likely take advantage of Böhm-Bawerk’s analysis, for he raises many subtle points that I have actually not included in this post. Despite one’s viewpoint of Böhm-Bawerk’s own theory of interest, reading his History and Critique of Interest Theories is definitely time well spent.

Originally released November 26, 2004.