Bernard Marx

Young tribal girls were lied to, treated as “human guinea pigs” without parental consent by a Gates-backed NGO

We’ve seen a lot of India in the news recently. A lot more than we usually do. There’s an apocalypse of sorts going on there, if the popular media is to be believed. But as is often the case, these reports are devoid of any context or perspective.

While the world’s media can’t get enough of India today, in its rush to support a narrative of terror about Covid-19, twelve years ago when there was a real story going on there, the world’s media was nowhere to be seen.

SOME BACKGROUND

In 2009, a Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF) funded NGO carried out unauthorised clinical trials of a vaccine on some of the poorest, most vulnerable children in the world. It did so without providing information about the risks involved, without the informed consent of the children or their parents and without even declaring that it was conducting a clinical trial.

After vaccination, many of the participating children became ill and seven of them died. Such were the findings of a parliamentary committee charged with investigating this wretched affair. The committee accused the NGO of “child abuse” and produced a raft of evidence to back up its claim. This entire incident barely registered on the radar of Western media.

PATH (formerly the Program for Appropriate Technology in Health) is a Seattle based NGO, heavily funded by BMGF but which also receives significant grants from the US government. Between 1995 and the time of writing (May 2021), PATH had received more than $2.5bn from BMGF.

In 2009, PATH carried out a project to administer the Human Papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine. The project’s aim was, in PATH’s own words, “to generate and disseminate evidence for informed public sector introduction of HPV vaccines”. It was conducted in four countries: India, Uganda, Peru and Vietnam. Another Gates-funded organization, Gavi, had originally been considered to run the project, but responsibility was ultimately delegated to PATH. The project was directly funded by BMGF.

Significantly, each of the countries selected for the project had a different ethnic population and each had a state-funded national immunisation program. The use of different ethnic groups in the trial allowed for comparison of the effects of the vaccine across diverse population groups (ethnicity being a factor in the safety and efficacy of certain drugs).

The immunisation programs of the countries involved provided a potentially lucrative market for the companies whose drugs were to be studied: should the drugs prove successful and be included on these countries’ state-funded national immunisation schedules, this would represent an annual windfall of profits for the companies involved.

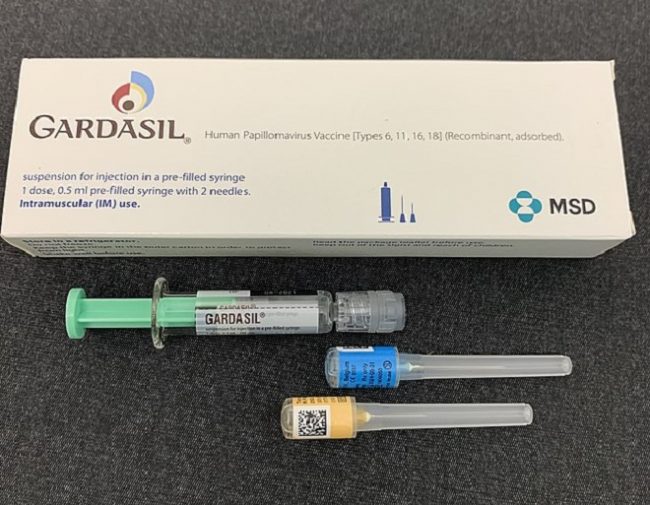

Two types of HPV vaccine were used in the trial: Gardasil by Merck and Cervarix by GlaxoSmithKline (GSK). In this article, we are going to examine PATH’s trial of Gardasil in India.

It’s worth noting here the relationship between BMGF and one of the companies whose drugs were being tested. In 2002, BMGF had, controversially, bought $205m worth of stocks in the pharmaceutical sector, a purchase which included shares in Merck & Co. The move had raised eyebrows because of the obvious conflict of interest between the foundation’s role as a medical charity and its role as an owner of businesses in the same sector.

The Wall Street Journal reported, in August 2009, that the foundation had sold its shares in Merck between 31st March and 30th June of that year, which would have been around the same time that the field trials of the HPV vaccine were starting in India. So for the entirety of this project (which was already in operation by October 2006), right up to its final field trials, BMGF had a dual role: as both a charity with a responsibility for care, and as a business owner with a responsibility for profit.

Such conflicts of interest have been a hallmark of BMGF since 2002. When Gates was making regular TV appearances last year to promote Covid-19 vaccination, giving especially ringing endorsements of the Pfizer-BioNTech effort, his objectivity was never brought into question. Yet his foundation is the part-owner of several vaccine manufacturers, including Pfizer, BioNTech and CureVac.

HPV VACCINE

The Gardasil HPV vaccine

HPV vaccine aims to prevent cervical cancer. Gardasil had been launched successfully by Merck in the US in 2006, but its sales suffered after a series of articles in American medical journals had judged that its risks outweighed its benefits. Especially damaging was an analysis of reports made to the CDC’s Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) about adverse reactions to Gardasil.

This analysis was published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) on August 19th 2009. The 12,424 adverse reactions which had been reported included 772 which were considered serious, 32 of which were deaths. Other reported serious side effects included autoimmune disorders, venous thromboembolic events (blood clots) and Guillain-Barré syndrome.

In the same edition of JAMA, Dr. Charlotte Haug, then editor-in-chief of the Journal of the Norwegian Medical Association, wrote,

Whether a risk is worth taking depends not only on the absolute risk, but on the relationship between the potential risk and the potential benefit. If the potential benefits are substantial, most individuals would be willing to accept the risks. But the net benefit of the HPV vaccine to a woman is uncertain. Even if persistently infected with HPV, a woman most likely will not develop cancer if she is regularly screened. So rationally she should be willing to accept only a small risk from the vaccine.”

Dr. Haug also noted, “When weighing evidence about risks and benefits, it is also appropriate to ask who takes the risk, and who gets the benefit”, in a clear dig at Gardasil manufacturer Merck.

Merck’s attempts to promote Gardasil had been controversial. Dr. Angela Raffle, one the UK’s leading experts on cervical cancer screening, described Merck’s marketing strategy as “a battering ram at the Department of Health and carpet bombing on the peripheries.”

Dr. Raffle was concerned that the push to mass vaccination would harm the successful screening programme which had operated in the UK since the 1960s.

“My worry is that the commercially motivated rush to make us panic into introducing HPV vaccine quickly will put us back and worsen our cervical cancer control programme.”

Professor Diane Harper

Professor Diane Harper, then of Dartmouth Medical School in New Hampshire, had led 2 trials of the vaccine and was adamant that Gardasil could not protect against all strains of HPV.

When Merck launched a huge public relations campaign in 2007 to persuade European governments to use the product to vaccinate all the continent’s young girls against cervical cancer, she said:

Mass vaccination programmes (would be) a great big public health experiment….We don’t know a lot of things. We don’t know the vaccine will continue to be effective. To be honest, we don’t have efficacy data in these young girls right now. We’re vaccinating against a virus that attacks women throughout their whole life and continues to cause cancer. If we vaccinate girls at 10 or 11 we won’t know for 20 to 25 years whether it is going to work or not. This is a big thing to take on.”

So at the time that PATH was carrying out its trials in India, Uganda, Peru and Vietnam, Gardasil was a controversial vaccine: its safety, efficacy and Merck’s attempts to promote it were being questioned, not by “anti-vaxxers” and “conspiracy theorists”, but by the international medical establishment and the respected mainstream media.

THE GIRLS OF KHAMMAM

Children of the Koya tribe, Khammam

Khammam district, in 2009, was a part of the eastern Indian state of Andhra Pradesh (boundary changes made in 2014 mean that today Khammam district belongs to the state of Telangana). The region is predominantly rural and is considered to be one of the poorest and least developed parts of India.

Khammam is home to several ethnic tribal groups,with some estimates putting its tribal population at about 21.5% (approximately 600,000 people). As is common for indiginous people throughout the world, the tribal groups of Khammam suffer from a lack of access to education. Consequently, their level of literacy is of a standard considerably lower than that of the region as a whole.

Some 14,000 girls were injected with Gardasil in Khammam district during 2009. The girls recruited for PATH’s project were between 10 and 14 years of age and all came from low-income, predominantly tribal backgrounds. Many of the girls did not reside with their families; instead they lived in ashram pathshalas (government-run hostels), which were situated close to the schools the children attended.

Professor Linsey McGoey, of the University of Essex, later stated she believed girls at ashram pathshalas had been targeted for the project as this was a way of:

side-stepping the need to seek parental consent for the shots.”

Although we have seen a lot of India in the news recently, coverage of this country and its affairs is usually low-key. Despite being home to almost one fifth of the world’s population, reporting on India is sparse.

Few of us are aware, for example, of its abysmal history of health and safety or its long-standing tradition of corruption in government.

Such failings have been taken advantage of by unscrupulous profit-seekers for decades. Western media only reports on the consequences of these actions when their magnitude is too great to ignore.

We learned that up to 7,000 people were killed and more than half a million were injured after being exposed to deadly methyl isocyanate gas, following a gas leak at the Union Carbide pesticide plant in Bhopal. But we learned nothing in the years leading up to it of the culture of poor standards and disregard for regulation which was ultimately responsible for the disaster.

So it was typical that PATH’s project to administer and study the effects of the HPV vaccine went unheralded in the West. Typical, too, that the same was true in India itself: the Indian media is no more renowned for its reporting on tribal groups than the Western media is for its coverage of Indians. Despite concerns expressed about the project in October 2009 by Sama, a Delhi-based NGO that advocates for women’s health, the matter remained absent from India’s news.

Members of the advocacy group Sama

This project, then, couldn’t have been more off-the-map had it taken place on the moon, and it remained so for several months until, early in 2010, stories began to filter out from Khammam that something had gone terribly wrong: many of the girls who had been involved in the trials had subsequently fallen ill and four of them had died.

In March 2010, members of Sama visited Khammam to find out more about the emerging stories. They were told that up to 120 girls had experienced adverse reactions, including epileptic seizures, severe stomach ache, headaches and mood swings. The Sama representatives remained in Khammam to investigate the situation further.

The involvement of Sama finally brought the matter to the attention of the Indian media and, amid a barrage of negative publicity, the Indian Council of Medical Research (IMCR) suspended the PATH project.

At this point the Indian Parliament’s Standing Committee on Health began an investigation into the affair.

On May 17th, Sama produced a damning report highlighting, among other things: that the trials had been promoted as a government immunisation programme and not a research project, that the girls had not been made aware that they could choose not to participate in the trials, and that parental consent had neither been asked for nor given in many cases.

The report stated that:

Many of the vaccinated girls continue to suffer from stomach aches, headaches, giddiness and exhaustion. There have been reports of early onset of menstruation, heavy bleeding and severe menstrual cramps, extreme mood swings, irritability, and uneasiness following the vaccination. No systematic follow up or monitoring has been carried out by the vaccine providers.”

Sama also disputed the Andhra Pradesh State Government’s claim that the deaths of four of the girls who had participated in the trials had nothing to do with vaccination.

THE PARLIAMENTARY COMMITTEE

Parliament House, seat of the Parliament of India, New Delhi

The wheels of bureaucracy are slow to turn. It was more than three years later, on 30th August 2013, when the report of the Indian Parliament’s Standing Committee on Health was finally published. Although many had expected the report to be a whitewash, it was anything but: it made for shocking reading.

The report excoriated both PATH and the IMCR, concluding that the “safety and rights of children were highly compromised and violated.” The committee found that PATH, despite operating in India since 1999, had no legal permission to do so. It noted that although the organisation had finally received a certificate from India’s Registrar of Companies in September 2009, this certificate itself was in breach of the law.

The report stated that:

PATH…has violated all laws and regulations laid down for clinical trials….its sole aim has been to promote the commercial interests of HPV vaccine manufacturers….This is a serious breach of trust…as the project involved the life and safety of girl children and adolescents who were mostly unaware of the implications of vaccination. The violation is also a serious breach of medical ethics.This act of PATH is a clear cut violation of the human rights of these girl children and adolescents. It is also an established case of child abuse.”

The committee charged that PATH had lied to it and had attempted to mislead it during the course of its investigation and recommended that the Indian Government report PATH’s violations of human rights to the WHO, UNICEF and the US Government.

The report declared that PATH’s whole scheme was a cynical attempt to ensure ongoing profits for Merck and GSK.

The choice of countries and population groups; the monopolistic nature, at that point of time, of the product being pushed; the unlimited market potential and opportunities in the universal immunisation programmes of the respective countries are all pointers to a well-planned scheme to commercially exploit a situation. Had PATH been successful…this would have generated a windfall profit for the manufacturers by way of automatic sale, year after year, without any promotional or marketing expenses. It is well known that once introduced to the immunisation programme it becomes politically impossible to stop any vaccination.”

It went on:

To achieve this end effortlessly, without going through the arduous and strictly regulated route of clinical trials, PATH resorted to an element of subterfuge by calling the clinical trials ‘Observational Studies’ or ‘a Demonstration Project’ and various such expressions. Thus the interest, safety and well being of subjects were completely jeopardized by PATH by using self-determined and self-servicing nomenclature which is not only highly deplorable but also a serious breach of the law of the land.”

Samiran Nundy, editor emeritus National Medical Journal of India

These charges were echoed by leading voices in India’s medical community. “It is shocking to see how an American organization used surreptitious methods to establish itself in India,” said Chandra M.Gulhati, editor of India’s influential Monthly Index of Medical Specialities, “(this) was not philanthropy”.

Samiran Nundy, editor emeritus of the National Medical Journal of India and a long-standing critic of corrupt practices in health, did not mince his words:

This is an obvious case where Indians were being used as guinea pigs.”

The standing committee’s report was also highly critical of the relationship between PATH and members of several of India’s health agencies, highlighting multiple conflicts of interest.

On the issue of informed consent, the committee confirmed the allegations made by Sama to be true, finding that the majority of consent forms weren’t signed by either the children or their parents, that many consent forms were postdated or not dated at all, that multiple forms had been signed by the same people (often the caretakers of the hostels the girls lived in) and that many signatures didn’t match the name on the form. It found that parents had not been given information on the necessity of vaccination, its pros and cons or its potential side effects.

No insurance was provided for any of the children in the event of injury and “PATH did not provide for urgent expert medical attention in case of serious adverse events.”

Further, PATH seriously contravened Indian health regulations by carrying out a clinical trial of a drug on children before first conducting a trial of the drug with adults as subjects.

Regarding the girls who had died, the committee criticized PATH, Indian medical authorities and the Andhra Pradesh State Government for summarily dismissing the link between their deaths and vaccination without conducting thorough investigations. By 2016, some 1,200 of the girls who had been subjects in the two HPV vaccine trials in India were reporting serious long-term side effects, more than 5% of the total cohort of 23,500. By then, the total number of deaths had risen to seven.

A DEATHLY SILENCE

Did a financial conflict of interest compromise the Guardian ?

This appalling breach of medical ethics and human rights went almost completely unmentioned outside India. The Indian Parliament’s Standing Committee on Health had literally accused an American NGO of child abuse, providing extensive evidence to support their charge, yet practically no mention of this was to be found anywhere in the Western media.

Popular science publications Nature and Science each contained a brief article about the debacle, but neither goes into any detail about PATH’s legal and ethical breaches. While the Science article is at least slightly critical, the Nature piece gives more space to a rebuttal of the charges by PATH director Vivien Tsu.

The way in which media around the world is funded by BMGF, and how this affects reporting about BMGF and the organisations it sponsors, deserves its own article. But it’s worth mentioning here that the BBC has received a total of $51.7m from BMGF, as of May 2021, and The Guardian has received $12.8m.

The Guardian, for all its claims to give a voice to the most vulnerable in the world, stayed curiously silent about the young girls of Khammam. That is, except for one article, published in October 2013, about six weeks after the release of the standing committee’s report.

The article was written not by one of the girls or one of their parents, not by one of the women from Sama who had advocated on the girls’ behalf, not even by one of the Indian parliamentarians who had been charged with investigating the affair.

No. It was written by an American man called Seth Berkely. Berkely is the CEO of Gavi, another BMGF funded health behemoth.

Seth Berkley, CEO GAVI

Berkely used his forum in The Guardian to claim that the girls who had died after being vaccinated in Khammam had committed suicide. Speaking about the 14,000 subjects involved in the trials, he said, “it would have been unusual if none of them went on to kill themselves.”

Compassion wasn’t the only element missing from his article. Not once did Berkley address the multiple breaches of law and ethics which had occurred or the role of PATH and that of his employers, the Gates Foundation, in his dismissal of this iniquity.

The Guardian began receiving funding from BMGF in August 2010. Prior to that arrangement, in 2007, the newspaper had published two separate articles which were critical of the lobbying tactics used by Merck to promote Gardasil and which questioned the efficacy of its use in mass vaccination programs.

Subsequent to their arrangement with Gates, all coverage by the Guardian of this drug (and of HPV vaccination in general) has been positive.

HOW THINGS TURNED OUT

BMGF headquarters, Seattle

The Indian government was reluctant to take any of the measures recommended by the committee. After all, there were huge amounts of money being made available to the state, institutions and individuals from organisations like PATH.

So no official reports of human rights violations were ever made by the Indian government to the WHO, to Unicef or to the American government, as had been recommended by the standing committee.

However, in 2017, it announced it would no longer accept grants from BMGF for its Immunisation Technical Support Unit, an organisation which provides “vaccination strategy advice” in relation to an estimated 27 million infants. Nevertheless, the Indian government continues to accept the foundation’s grants in other areas.

Merck, and their HPV vaccine Gardasil, have done very well since the dismal events recounted in this article. The Khammam scandal never really affected the company, due to a lack of awareness about it outside India. In 2018 alone, Gardasil sales amounted to more than $3bn, thanks to its inclusion on immunisation schedules around the world, and its launch that year in China.

PATH has never been better. Just like Merck, the lack of reporting about what happened in Khammam meant the organisation didn’t suffer. Since 2010, it has continued to receive huge funding from BMGF and, to a lesser extent, the US Government. During this period, BMGF has provided PATH with more than $1.2bn in funding.

The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation has continued expanding its web of influence. Describing the organisation’s practices around the time of the events outlined here, Jacob Levich said:

In essence, BMGF would buy up stockpiled drugs that had failed to create sufficient demand in the West, press them on the periphery at a discount, and lock in long-term purchase agreements with Third World governments.”

The foundation has since moved on to even more lucrative pastures. The Covid-19 pandemic has really pushed BMGF to centre stage. Gates himself has seen his public profile and political influence grow to an extent that would have been unimaginable even in 2019.

Despite his lack of either scientific qualifications or an electoral mandate, he regularly presses the need for mass global vaccination with products made by the companies he owns, using platforms given to him by the media outlets he funds.

And the girls of Khammam?

Well, those poor children and their plight wasn’t even widely known outside of India back in 2010. To say they had been forgotten would be to imply that anybody knew about them or cared about them in the first place.