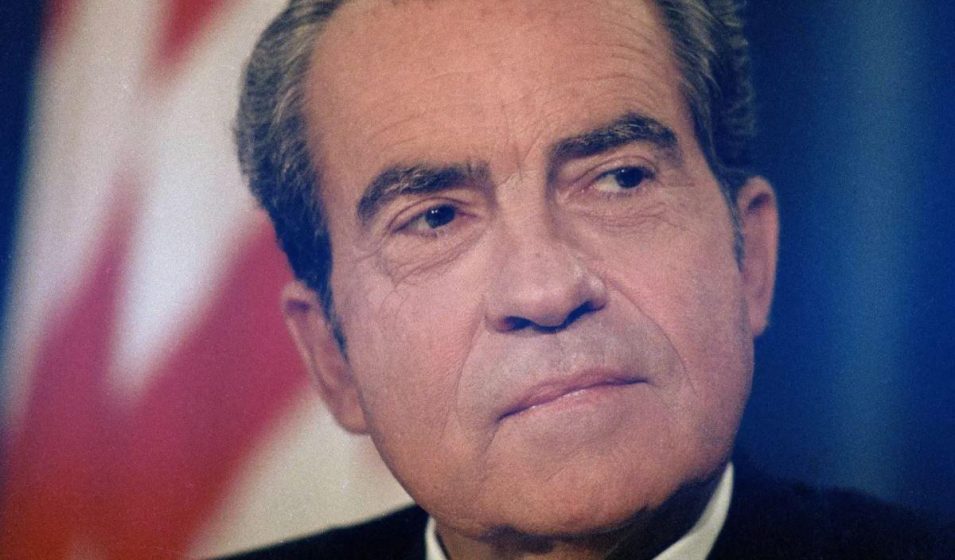

Because August 15, 1971, the US dollar has been entirely severed from gold. President Richard Nixon suspended the most crucial part of the Bretton Woods system, which had been in result since the end of World War II. Nixon revealed that the US would no longer redeem dollars for gold for the last staying entities that could: foreign federal governments. Gold redemption had been made prohibited for everyone else, so this action lastly ended any semblance of a gold standard for the United States dollar.

In Crisis and Leviathan, Robert Higgs demonstrated how in the twentieth century the United States federal government grew in size and scope mainly during crisis durations like wars or financial depressions. The powers gotten during those durations were often advertised as “short-term,” but history reveals that governments rarely relinquish powers. This “ratchet effect” uses to the method Nixon “momentarily” suspended gold redemption in 1971– the resulting routine of unbacked fiat dollars remains in result today.

What Was the Bretton Woods System?

The Bretton Woods system was developed by the Allied countries, led by the United States, near completion of The second world war as a postwar worldwide monetary order. The United States dollar would become the world’s reserve currency, which foreign federal governments could redeem for gold, even though United States residents might not. This prohibition was not new for US residents, because Franklin D. Roosevelt forbade personal ownership of gold coins and bullion in 1933.

To get foreign governments to join the contract, the United States promised to redeem dollars for gold at $35 per ounce, which limited the level to which the supply of dollars might be broadened. International trade was slow to restart after World War II, which meant that the Bretton Woods system of gold exchange was not completely checked until the late 1950s. Yet, even by this time, US inflation indicated that Japan and nations in Western Europe were holding a reserve currency that was falling in value, particularly relative to the guaranteed $35-per-ounce rate of gold.

The US could only use diplomatic pressure to slow the foreign federal governments’ requests for gold redemption. Even so, the US lost about 55 percent of its stock of gold from the early 1950s to the end of the Bretton Woods system in 1971.

In a desperate effort to preserve the Bretton Woods system in 1968, the US attempted to implement a “two-tier gold market” such that central banks worldwide would participate in one market that would look for to keep the $35-per-ounce dollar-to-gold ratio, and would not buy or sell in the other tier: the private, free gold market.

This, obviously, quickly fell apart. By 1971, President Nixon could not include the results of the financial inflation used to spend for the Vietnam War and Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society programs (including Nixon’s own growths). Amidst a host of desperate interventions such as new tariffs and wage and rate controls, Nixon likewise “momentarily” suspended gold convertibility. He looked for to “safeguard the position of the American dollar as a pillar of monetary stability around the globe.”

The dollar was completely severed from any product support, making it a simply fiat money. The Federal Reserve might now pump up with no regard for redemption needs from civilians, services, foreign governments, or foreign reserve banks.

The Result: Inflation

Anyone needs to have had the ability to anticipate the effects of this occasion. A federal government with an all set buyer of debt in the form of an unrestrained reserve bank can spend much more, because the redistributive effects of inflation are less obvious than taxation. Gold redemption was a strict limiting factor for the Fed– now the only restrictions are political and subjective, despite the appearance of technical competence at the Fed.

The risk of lacking gold has been changed with the softer, lagged-consequence question: “To what level will voters tolerate price boosts and monetary crises?” And even the negative political repercussions may be made use of via Cantillon effects by producing and rewarding a picked set of powerful, politically connected winners at the cost of a less effective, propagandized population of losers.

The repercussions of the closure of the Bretton Woods system and the staying façade of sound money it represented are well recorded. Time series of almost any macroeconomic statistic reveal a “structural break,” i.e., an abrupt modification in the trajectory of the series, around 1971 or shortly after. A website with the tongue-in-cheek URL WTFHappenedIn1971.comoffers numerous such examples. Measures of financial inflation, cost boosts, inequality, monetary crises, saving rates, federal government spending, federal government size and scope, social/cultural indications, imprisonment rates, and even meat usage and the variety of lawyers all have inflection points in the early 1970s.

Financial Crisis and Leviathan

Besides the economic repercussions of unhinged reserve banks, we should also comprehend the means by which the government was able to obtain a lot control over cash. Looking at episodes like Woodrow Wilson’s creation of the Federal Reserve, FDR’s confiscation of gold, and Nixon’s cancellation of Bretton Woods, as well as all of the other times the government chipped away at sound money, we discover a commonality. Crises, real or simply viewed, are made use of each time.

Wilson rode the wave of worry of monetary panics and the concern for farmers desperate for credit that had been stirred up by William Jennings Bryan and other progressives. Wilson stressed the “urgent requirement that special arrangement be made likewise for facilitating the credits needed by the farmers of the nation” and painted an apocalyptic image of a world without his suggested banking system reforms:

I need not stop to inform you how basic to the life of the Nation is the production of its food. Our ideas might normally be focused upon the cities and the hives of market, upon the sobs of the crowded market place and the clangor of the factory, however it is from the peaceful interspaces of the open valleys and the free hillsides that we draw the sources of life and of prosperity, from the farm and the cattle ranch, from the forest and the mine. Without these every street would be quiet, every office deserted, every factory fallen under disrepair.

FDR was the master of crisis exploitation. Executive Order 6102 begins in this manner:

By virtue of the authority vested in me by Section 5 (b) of the Act of October 6, 1917, as modified by Area 2 of the Act of March 9, 1933, entitled “An Act to offer relief in the current national emergency situation in banking, and for other purposes,” in which amendatory Act Congress stated that a major emergency exists, I, Franklin D. Roosevelt, President of the United States of America, do state that stated nationwide emergency still continues to exist and pursuant to said section do thus forbid the hoarding of gold coin, gold bullion, and gold certificates within the continental United States by individuals, collaborations, associations and corporations.

Just one month previously, FDR had mandated a bank vacation, suspending all withdrawals of gold from banks. His proclamation mentioned a “national emergency” due to “significantly substantial speculative activity” and “heavy and baseless withdrawals of gold and currency from our banking organizations for the purpose of hoarding.”

Practically forty years later, we see speculators being used as scapegoats once again. In Nixon’s announcement, he implicated “international cash speculators” of benefiting off monetary crises and “waging an all-out war on the American dollar” as if they were the ones triggering the volatility in forex markets and the wholesale drain of gold from the United States, not the United States federal government’s own irresponsible profligacy.

In all of these episodes, the United States presidents framed the power grab as a needed and sometimes temporary response to a crisis. Financial stresses, the hazard of hunger, gold hoarders, and external speculative enemies were all utilized as a basis and cover for doing what federal governments have done for centuries: debasement, coin clipping, and cash printing for the purpose of surreptitious extraction of wealth from a population.

Only the most naïve might see the history of cash and banking in the US as anything aside from a cog of federal government growth, specifically in the twentieth century. Even current Fed actions follow the exact same pattern.

Conclusion

The Bretton Woods system was the last remaining vestige of the gold standard. As weak as it was, it limited the Fed’s capability to broaden the supply of dollars due to the possibility of other federal governments redeeming their dollars for gold. When Nixon suspended the key element of the global agreement, he introduced a new age of reserve bank financial policy unhindered by any promise to redeem dollars for a certain weight of gold.

The economic and cultural consequences of this occasion have been disastrous: even more inflation; exacerbated inequality through Cantillon impacts; more government, both in size and scope; higher rates of time choice; extreme financial crises and business cycles; and, naturally, greater rates.

Completion of the Bretton Woods system followed the same pattern all other episodes in the death of the gold requirement followed. A crisis (real or simply viewed) was exploited to reveal a “temporary” step or an “important reform” of the existing system. The larger picture shows a federal government that has finally gained 100 percent control over money and banking in the type of unbacked fiat cash provided by an unrestrained central bank.