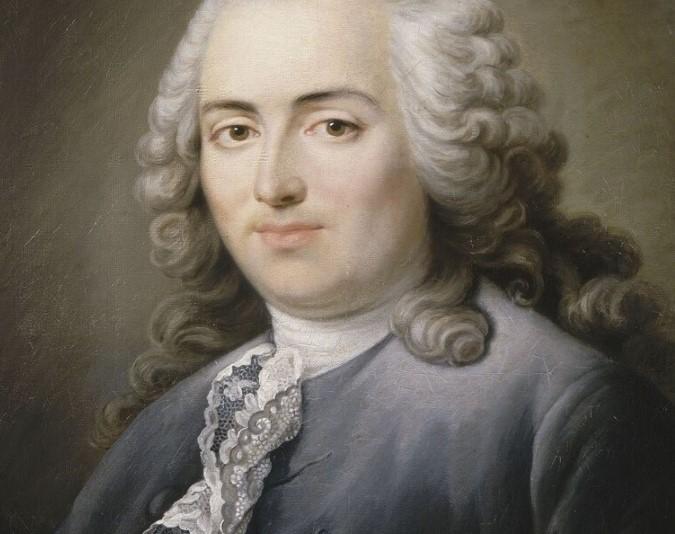

Murray Rothbard sees the eighteenth-century French economic expert and administrator Anne-Robert-Jacques Turgot as a terrific and admirable figure, however David Graeber and David Wengrow do not agree. In their recently published The Dawn of Everything(Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2021), they provide Turgot as a force for evil. His concepts provided a validation for a false sense of Western supremacy to individuals apparently less civilized and because method provided assistance to wars of conquest versus them. In this week’s column, I ‘d like to consider their account of Turgot’s contrast of modern with primitive society.

Graeber, who died right before the book was published, and Wengrow are left-anarchist anthropologists, bitterly opposed to capitalism, which they view as an oppressive system. Their primary grievance against industrialism is that it compels people to be efficient. The system pressures people to work more and more hours in order to acquire more product items, although they would be better with more leisure and a simpler life. In brief, capitalism stultifies human life.

Rothbard’s opinion of Turgot could not be more different:

In continuing to more in-depth analysis of the market procedure, Turgot explains that self-interest is the prime mover of that procedure, and that … specific interest in the free market must constantlycoincide with the general interest. The buyer will choose the seller who will give him the best price for the most ideal item, and the seller will offer his finest merchandise at the lowest competitive cost. Governmental limitations and unique opportunities, on the other hand, oblige customers to buy poorer items at high prices.

Turgot concludes that “the basic freedom of trading is therefore … the only ways of guaranteeing, on the one hand, the seller of a price adequate to encourage production, and, on the other hand, the customer of the best product at the lowest rate.” Turgot concluded that federal government ought to be strictly restricted to safeguarding people versus “excellent injustice” and the nation versus invasion. “The federal government ought to always protect the natural liberty of the buyer to buy, and the seller to offer.”

Individuals under commercialism freely pursue their objectives; setting the exigencies of nature aside, they aren’t required to do anything.

Why do Graeber and Wengrow take such an unfavorable view of the free enterprise and its defender Turgot? As they tell the tale, Turgot reacts to Madame de Graffigny and other French authors who worry the liberty possessed by native individuals untouched by civilization:

Yes, Turgot acknowledged, “all of us love the concept of liberty and equality”– in principle. However we must consider a larger context … the liberty and equality of savages is not a sign of their superiority; it suggests inferiority, considering that it is only possible in a society where each household is largely self-sufficient and, therefore, where everyone is equally poor … As societies develop, Turgot reasoned, innovation advances. Natural differences in skills and capacities between individuals … become more substantial, and eventually they form the basis for an ever more intricate division of labour. We progress from simple societies … to our own complex “commercial civilization,” in which the hardship and dispossession of some– nevertheless lamentable it might be– is nonetheless the required condition for the prosperity of society as a whole. (p. 60)

This account of Turgot totally misunderstands his argument. Turgot is not saying that the division of labor decreases liberty but rather that it increases productivity. It does so by making the most of specialization, and doing this results in inequality due to the fact that natural differences will develop even more. However Turgot doesn’t claim that the free enterprise leads to a hierarchical society in which some people must dominate others. Why would it? Graeber and Wengrow do not inform us.

They may counter this with two points. Initially, they might deny that primitive societies were less efficient than contemporary industrial societies, but this does not seem possible. They do argue that in lots of primitive societies, most people had an abundance of items, however even if that holds true, it does not follow that an economy that uses the division of labor isn’t more productive: the argument for the higher productivity of the division of labor doesn’t depend upon the property that a society without this feature is impoverished.

The 2nd point that they may raise against Turgot is this. According to their anthropological evidence, in some primitive societies there weren’t large numbers of bad people, but it is definitely the case that there are large numbers of poor people in industrial societies. Does not this program that primitive societies were in this regard better?

This argument neglects the truth that, compared with the modern-day world, primitive modes of social company have the ability to support much smaller numbers of individuals. If population increased, an egalitarian primitive society would be unable to cope with the added problem; only the department of labor makes it possible for the large populations of the modern world to endure. Readers will no doubt recall that Mises makes a parallel argument in response to charges that the Industrial Transformation aggravated conditions for the masses (see Human Action, p. 617). And if large numbers of poor individuals yet stay, the build-up of capital that the free market fosters results in making them much better off. Graeber and Wengrow make an odd error in presuming from Turgot’s point that the general prosperity of the contemporary world is higher than in earlier times, even though there are bad individuals, that he thinks that the increased prosperity needs the presence of bad people.

Turgot makes another argument to which Graeber and Wengrow have no appropriate response. If you wish to enforce equality in modern-day conditions, the “just alternative … would be huge, Inca-style state intervention to develop a harmony of social conditions; an enforced equality which could only have the impact of squashing all effort, and, therefore, lead to economic and social catastrophe” (paraphrased on p. 60).

Graeber and Wengrow tell us about numerous remarkable findings that anthropologists have actually made in the last few years, but they do not comprehend that their criticisms of Turgot and the free market rest on primary financial misconceptions. For them, sociology is the master science, and they look down with condescension on those oblivious of its secrets. Like Robert Browning’s Abt Vogler, they say: “The rest may reason, and welcome;’t is we artists understand.”