It is stated that a variety of years earlier, when Bill Buckley was at the beginning of his profession of college-speaking, and somewhat more tolerant of libertarians than he is today, he when composed two names on the blackboard consequently well dramatized the point that trainees in his audience were being presented with just one side of the excellent world-forming argument between industrialism and socialism. The name of the protector of democratic socialism– I think it was Harold Laski, potentially John Dewey– was acknowledged by the majority of those present.

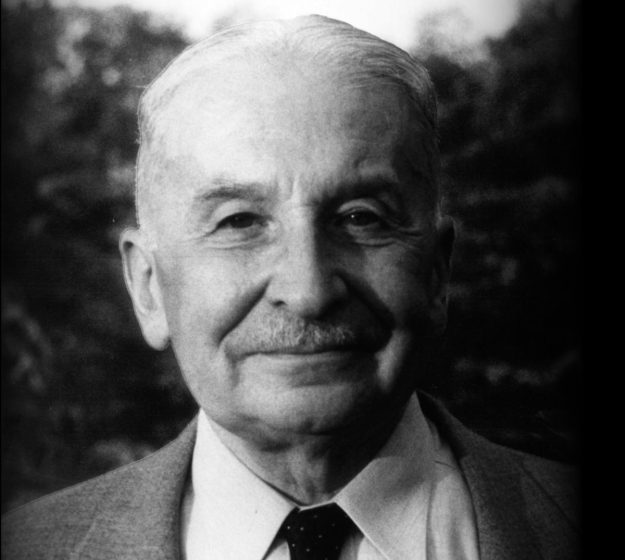

The name of Ludwig von Mises was totally unknown to them. Needless to say, the scenario has actually not basically enhanced since then (unless maybe in the sense that a lot of university student would now acknowledge the name of William F. Buckley, Jr.). How has it been possible that the terrific majority of economics and social science trainees, even at elite American universities, are totally not familiar with Mises? Even the New York City Times, in its notification at the time of his death in October 1973, called Mises “among the foremost economic experts of this century,” and Milton Friedman, though from a totally different tradition of economic idea, has called him “among the excellent economists of all time.”

However Mises was even more than an excellent financial expert. Throughout the world, amongst educated individuals– in German-speaking Europe, in France, in Britain, in Latin America, in our own country– Mises was famous as the great twentieth century champ of a school of idea which might be stated to have a particular historic significance and a certain intellectual respectability: the one that began with Adam Smith, David Hume, and Turgot, and consisted of Humboldt, Bentham, Benjamin Continuous, Tocqueville, Acton, Böhm-Bawerk, William Graham Sumner, Herbert Spencer, Pareto, and many others. Offhand, one would have believed that this acknowledged position alone would have entitled Mises to being provided within the “pluralistic” setting of left-liberal Academe.

And after that there were Mises’s scientific accomplishments, which were remarkable. For example, it is yielded on all sides that in the whole discussion focusing on the practicality of a system of central economic planning, Mises played the crucial role. Rather potentially the fantastic intellectual scandal (still unadmitted) of the previous century has been that the huge international Marxian motion, consisting of thousands upon countless professional thinkers in all fields, was for generations content to discuss the entire problem of capitalism vs. socialism exclusively in terms of the supposed defects of commercialism. The concern of how, and how well, a socialist economy would operate, was prevented as taboo.

It was Mises’s achievement– and an indication of his excellent self-reliance of mind– to have brushed aside this pious “one-just-doesn’t-speak-of-such-things,” and to have provided thoroughly and arrestingly the problems inherent in attempting reasonable economic calculation in a situation where no market exists for production items. Anybody acquainted with the structural problems with which the more advanced Communist nations are constantly dealt with and with the dispute over “market socialism,” will perceive the significance and continuing relevance of Mises’s work in this field alone.

How then can we represent the fact that those who handled to take a Laski and a Thorstein Veblen– and even a Walter Lippmann and a Kenneth Galbraith– seriously as important social theorists in some way could never ever bring themselves to familiarize their trainees with Mises or to reveal him the marks of public recognition and regard that were his due (he was, for instance, never ever president of the American Economic Association)? A minimum of part of the response, I believe, depends on what Jacques Reuff, in a warm homage, called Mises’s “intransigence.” Mises was a total doctrinaire and an unrelenting and implacable fighter for his doctrine. For over sixty years he was at war with the spirit of his age, and with each of the advancing, triumphant, or simply modish political schools, left and right.

Decade after decade he combated militarism, protectionism, inflationism, every variety of socialism, and every policy of the interventionist state, and through the majority of that time he stood alone, or near to it. The totality and sustaining intensity of Mises’s battle could only be sustained from an extensive inner sense of the truth and supreme value of the ideas for which he was struggling. This– in addition to his character, one supposes– helped produce a definite “arrogance” in his tone (or “apodictic” quality, as some of us in the Mises workshop fondly called it, utilizing among his own preferred words), which was the last thing academic left-liberals and social democrats could accept in a protector of a view they considered just marginally worthy of toleration to begin with. (This would mostly account, I believe, for the somewhat greater acknowledgment that has been accorded Friedrich Hayek, even before his significantly should have Nobel Prize. Hayek is temperamentally much more moderate in expression than Mises ever was, choosing, for instance, to avoid the old motto of “laissez faire.” And it is hard to imagine Mises making such a gesture as Hayek carried out in dedicating The Roadway to Serfdom “to socialists of all celebrations.”)

But the absence of recognition seems to have affected or deflected Mises not in the least. Rather, he continued his work, decade after decade: building up contributions to economic theory; establishing the theoretical structure of the Austrian School; and, from his understanding of the laws of economic activity, elaborating, remedying, and bringing up to date the fantastic social philosophy of classical liberalism.

Now, within the classical liberal custom, differences may be drawn. One very essential one is in between what might be described “conservative” and “extreme” liberals. Mises belonged to the 2nd classification, and on this basis might be contrasted to writers, for instance, such as Macaulay, Tocqueville, and Ortega y Gasset. There was extremely little of the Whig about Mises. The vaunted virtues of upper class; the supposed need for a religious basis for “social cohesion;” the respect for custom (it was in some way always authoritarian traditions that were to be reverenced, and never ever the customs of free thought and rebellion); the worry of the emerging “mass-man,” who was ruining things for his intellectual and social betters; the entire cultural review that later supplied a substantial foothold for the attack on the customer society– these discovered no place in Mises’s thinking.

To take an example, Tocqueville, in Democracy in America, at one point cries out: “Nothing conceivable is so minor, so insipid, so crowded with paltry interests– in a word, so anti-poetic– as the life of a guy in the United States.” Whether or not this judgment holds true, Mises would never ever have bothered to make it. As an utilitarian liberal, he had more regard for the requirements by which normal individuals judge the quality of their own lives. It is highly doubtful that Mises felt any of the qualms of liberals like Tocqueville at the Americanization of the world. (In truth, their attitude towards America would be a good rough criterion for categorizing classical liberals as “radical” or “conservative.”)

Mises, then, was a radical liberal, in the line of the Philosophical Radicals and the guys of Manchester. All the components of extreme liberalism exist: first of all, and a lot of standard, his uncompromising rationalism, reiterated again and again. (Symptomatic of Mises’s avoidance of whatever he would consider mystical and obscurantist in social thought is the truth that, to my knowledge, he never ever in all his published works as soon as points out Edmund Burke except in the context of someone who, in alliance with authors like de Maistre, was ultimately a philosophical opponent of the establishing liberal world.)

There is his utilitarianism, taking the end of politics to be not “the excellent,” but human well-being, as men and women separately specify it on their own. There is his championing of peace, which in the tradition of those nineteenth-century liberals most closely identified with the doctrine of complete laissez faire– Richard Cobden, John Bright, Frédéric Bastiat, and Herbert Spencer– he bases upon the financial base of open market. And, more unexpected, there is in Mises an essentially democratic issue and, in an essential sense, an egalitarianism, such that this needs unique remark.

Mises’s basically democratic and egalitarian out-look is not, obviously, to be understood in terms of belief in some innate equality of talents or in equality of earnings. When Mises discusses the terrific concern of equality he does not want a future fantasy paradise, where each will definitely count for one and none for more than one, however rather the empirical conditions under which people have actually hitherto found themselves in different societies.

What have actually been the conditions of class, status, degree, and opportunity in the history of humanity, and what distinction does commercialism make? The history of pre-capitalist societies is among slavery, serfdom, and caste- and class-privileges in the most degrading types. It is history made by slave-owners, warrior-nobles, and eunuch-makers, by kings, their girlfriends, and courtiers, by priests and other Mandarin-intellectuals– by parasites and oppressors of all descriptions. Commercialism moves the entire center of mass of society (“The World Turned Upside Down,” as Lord Cornwallis’s troops dipped into Yorktown).

In the threadbare however true and sociologically immensely important statement: every dollar, whether in the possession of someone absolutely lacking in the social beautifies, of someone of “mean birth,” of a Jew, of a black, of someone nobody ever even become aware of, is the equal of every other dollar and commands services and products on the market which talented people need to structure their lives to offer. As Marx and Engels observed, the market breaks down every Chinese Wall and levels the world of status and standard opportunity that the West acquired from the Middle Ages.

It is the battering ram of the terrific democratic revolution of contemporary times. Mises kept that the pseudorevolution which socialism would cause is far more likely to result in the reemergence of the society of status and the re-degradation of the masses to the position of pawns, controlled by an elite which would designate itself the title role in the heroic melodrama, Male Consciously Makes His Own History.

As far as the quality and quality of Mises’s thinking goes, my own view is that he is able to penetrate to the heart of important questions, where other writers normally tire their capabilities on peripheral points. Some of my favorite examples are his discussions of “employee control” (which promises to become the chosen social system of the Left in many Western nations), and of Marxist social viewpoint (which Mises deals with in a number of his books, a lot of thoroughly and trenchantly in Theory and History.)

In the combination in this short conversation of fantastic intellectual scope, extensive thinking, and the proud defense of classical liberal worths, the reader can glance something of the distinctive character of Mises as social theorist.

No gratitude of Mises would be complete without stating something, however insufficient, about the guy and the individual. Mises’s immense scholarship, bringing to mind other German-speaking scholars, like Max Weber and Joseph Schumpeter, who seemed to work on the principle that one day all encyclopedias might extremely well simply disappear from the shelves; the Cartesian clearness of his presentations in class (it takes a master to present a complex subject merely); his regard for the life of reason, apparent in every gesture and glance; his courtesy and kindliness and understanding, even to beginners; his real wit, of the sort proverbially bred in the fantastic cities, akin to that of Berliners, of Parisians and New Yorkers, just Viennese and softer– let me just state that to have, at an early point, come to know the great Mises tends to create in one’s mind life-long requirements of what a perfect intellectual must be.

These are requirements to which other scholars whom one encounters will practically never ever be equivalent, and evaluated by which the common run of university teacher– at Chicago, Princeton, or Harvard– is just a joke (but it would be unfair to judge them by such a measure; here we are speaking about 2 totally various sorts of humans). It was completely fitting for Murray Rothbard, in the obituary he wrote for Mises in Libertarian Forum, to append these lines from Shelley’s Adonais, and it is fitting for us to recall them in the year of Mises’s centenary:

For such as he can lend– they obtain not

Glory from those who made the world their victim;

And he is gathered to the kings of idea

Who waged contention with their time’s decay,

And of the past are all that can not die.

Finally, for the severe reader of politics and social philosophy who has never studied Mises my suggestions would be to make the omission great as soon as possible: it will conserve a lot of otherwise squandered effort on the roadway to fact in these matters. Liberalism or Bureaucracy would be an excellent start; or, for those with a special interest in twentieth century history, Omnipotent Federal government; or his Socialism, which remains for me the finest book I have actually ever checked out in the social sciences. Considering the definitely critical place America has in Western civilization today, it would genuinely be a catastrophe if a couple of establishment professors was successful in keeping intelligent young Americans from familiarizing themselves with the abundant heritage of concepts left us by Ludwig von Mises.

A variation of this short article appeared in the October 1981 issue of the Libertarian Evaluation.