“He [Lee] was a superb specimen of manly grace and elegance…There was about him a stately dignity, calm poise, absolute self-possession, entire absence of self-consciousness, and gracious consideration for all about him that made a combination of character not to be surpassed…His devotion to his invalid wife, who for many years was a martyr to rheumatic gout, was pathetic to see…His tenderness to his children, especially his daughters, was mingled with a delicate courtesy which belonged to an older day than ours – a courtesy which recalls the preux chevalier of knightlier times.”[1] – Margaret J. Preston

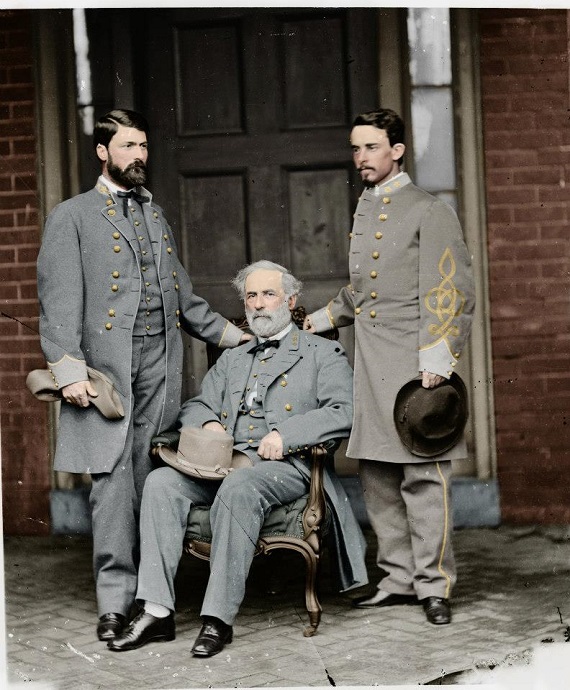

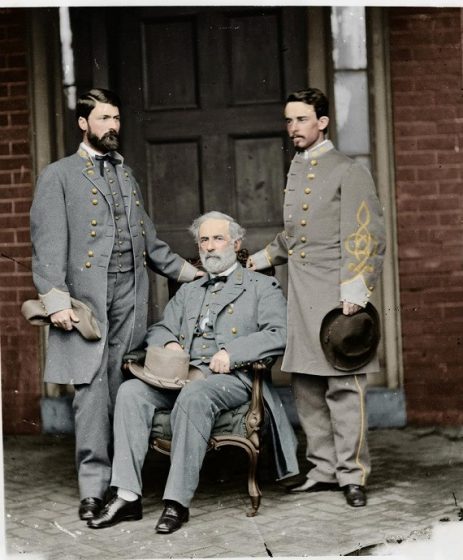

On 30 June, 1831, Robert E. Lee married Mary Anna Randolph Custis, the great-granddaughter of George and Martha Washington.[2] They had seven children: George Washington Custis Lee, Mary Custis Lee, William Henry Fitzhugh Lee, Anne Carter Lee, Eleanor Agnes Lee, Robert E. Lee Jr., and Mildred Childe Lee. Like all children, the Lees had nicknames. Custis was “Boo,” Mary was “Mee,” W.H.F. was “Rooney,” Anne was “Annie,” Eleanor was Agnes or “Wiggy,” R.E. Lee the younger was “Rob,” and Mildred was “Precious Life.”[3]

When Lee was still a young man and Custis was still a little boy, Lee returned home to Arlington from his post of duty for a Christmas visit and decided to go for stroll. He heard a crunching noise behind him, turned, and saw little Custis carefully placing his feet into the holes Lee’s boots had left in the snow. Given the difference in their height, this took all of young Custis’s attention and effort. According to Lee, this left an indelible impression upon his mind: “I learned a lesson then and there which I never afterwards forgot. ‘My good man,’ I said to myself, ‘you must be careful how you walk and where you go, for there are those following after you who will set their feet where yours are set.’”[4] When he was home, Lee loved to play with his children and read to them. The best English classics were always nearby, and he read them Sir Walter Scott’s novels so often that they knew them by heart.[5]

Found among Lee’s personal papers after his death was the following advice to himself: “Private and public life are subject to the same rules; and truth and manliness are two qualities that will carry you through this world much better than policy, or tact, or expediency, or any other word that was ever devised to conceal or mystify a deviation from a straight line.”[6] Another note to himself read: “There is a true glory and a true honour: The glory of duty done – the honour of the integrity of principle.”[7] A man who writes such notes for himself to meditate upon is unlikely to avoid sharing that wisdom with his offspring. Alas, the oft-quoted letter to Custis extolling the virtues of frankness, honesty, courage and duty is a forgery.[8]

As a soldier, Lee was often called upon to try and raise his children via letter. From his post of duty out west, he wrote to Mrs. Lee on 5 June, 1839:

“You do not know how much I have missed you and the children, my dear Mary. To be alone in a crowd is very solitary. In the woods I feel sympathy with the trees and birds, in whose company I take delight, but experience no pleasure in a strange crowd. I hope you are all well and will continue so, and therefore must again urge you to be very prudent and careful of those dear children. If I could only get a squeeze at that little fellow turning up his sweet mouth to ‘Keese baba!’ You must not let them run wild in my absence, and will have to exercise firm authority over all of them. This will not require severity or even strictness, but constant attention and an unwavering course. Mildness and forbearance, tempered by firmness and judgment, will strengthen their affection for you, while it will maintain your control over them.”[9]

In a letter from about the same time, Lee wrote: “Oh, what pleasure I lose in being separated from my children! Nothing can compensate me for that!”[10] He later counselled Rooney:

“I cannot go to bed, my dear son, without writing a few lines…You and Custis must take great care of your kind mother and dear sisters when your father is dead. To do that, you must learn to be good. Be true, kind, and generous, and pray earnestly to God to you to keep His Commandments ‘and walk in the same all the days of your life.’ I hope to come on soon and see that little baby you have got to show me. You must give her a kiss from me, and to all the children, and to your mother and grandmother.”[11]

After the war, Lee chanced to see a group of children playing marbles. One of them, a boy, accused his opponent, a girl, of cheating. Her brother took offense to this, and the two lads resolved to settle their dispute through fisticuffs. The little girl tearfully begged the General to make them stop. Lee later told a friend of his efforts at peacemaking: “I argued, I remonstrated, I commanded; but they were like two young mastiffs, and never in all my military service had I to own myself so perfectly powerless. I retired beaten from the field and let the little fellows fight it out.”[12] One can’t help wondering if his own boys ever quarreled so fiercely and how their father tamed them.

In a letter to Custis written just after Christmas of 1851, Lee wrote: “May you have many happy years, all bringing you an increase of virtue and wisdom, all witnessing your prosperity in this life, all bringing you nearer everlasting happiness thereafter. May God in His great mercy grant me this my constant prayer.”[13] Lee must have been proud when Custis graduated from West Point in 1854, for the younger man’s assignment to the Corps of Engineers placed him in the top of his class.[14]

Lee had always been a religious man, and had habitually attended morning services, but he had not been baptized as a member of any denomination. This he remedied on 17 July, 1853, when he accompanied Mary and Annie to Christ Church in Alexandria and the three were confirmed by the Episcopal Bishop of Virginia.[15] Four years later, Lee wrote to a friend describing his joy at Robert Jr.’s decision to be confirmed in the Episcopal Church: “I know you will sympathize in the joy I feel at the impression made by a merciful God upon the youthful heart of dear little Rob.”[16]

In May of 1860, Lee learned that his first grandchild had been born, a boy whom Rooney and Charlotte decided to name after the General. He wrote Rooney on June 2nd: “I wish I could offer him a more worthy name and a better example. He must elevate the first, and make use of the latter to avoid the errors I have committed. I also expressed the thought [in a separate letter to Charlotte] that under the circumstances you might like to name him after his great-grandfather, and wish you both, ‘upon mature consideration,’ to follow your inclinations and judgment. I should love him all the same, and nothing could make me love you two more than I do.”[17]

When Virginia seceded in 1861, Lee wrote to his sister: “I have not been able to make up my mind to raise my hand against my relatives, my children, my home. I have therefore resigned my commission in the Army, and save in defence of my native State…I hope I may never be called on to draw my sword.”[18] Lee must have known his sons would follow Virginia even if he did not, to say nothing of his wife and daughters, who were all solidly in the Old Dominion’s camp.

In November of 1863, the General wrote a letter to his wife telling her about a ten-minute conversation he’d had with a soldier’s wife who had traveled north from Abbeville, South Carolina in order to bring her husband a new suit of clothes. Lee called her “an admirable woman” and praised her warmly for her skill as a seamstress and her dedication to the cause of independence. He also teased his daughters about their sewing skills.[19] Lee always loved playfully teasing his children. It was his way of showing his affection. “We all loved that attention from him. He never teased any one whom he did not like.”[20]

From West Point in 1853, Lee wrote to Annie: “I am told you are growing very tall, and I hope very straight.”[21] Crooked character would not do. Nine years later, during the second autumn of the War Between the States, Lee learned that Annie had died from a prolonged illness. He was heartbroken, although he refused to display his sorrow to his staff and completed his day’s duties as army commander before allowing himself to address his anguish. According to his aide, Walter Taylor: “I then left him, but for some cause returned in a few moments, and with my accustomed freedom entered his tent without announcement or ceremony, when I was startled and shocked to see him overcome with grief, an open letter in his hands.”[22] Lee wrote to Mrs. Lee on 26 October, 1862: “I cannot express the anguish I feel at the death of our sweet Annie. To know that I shall never see her again on earth…is agonizing in the extreme. But God in this, as in all things, has mingled mercy with the blow, in selecting that one best prepared to leave us.”[23] To Daughter Mary, he wrote one month later: “I have always counted, if God should spare me a few days after this War is ended, that I should have her with me, but year after year my hopes go out, and I must be resigned.”[24] After the war, the citizens of the town in which Anne died decided to mark her grave specially and wrote to General Lee asking for her date of birth and an inscription for the monument. Lee gratefully replied: “The latter are the last lines of the hymn she asked for just before her death.”[25] The inscription reads: “Perfect and true are all His ways, whom Heaven adores and Earth obeys.”[26]

Despite his love for his family, Lee assiduously avoided anything that smacked of nepotism. All three of the General’s sons followed him into the army at the outbreak of war, but none of them rose in rank through his influence. Rooney earned his promotions in battle, Custis owed his to President Davis, and the General refused to make Rob a member of his staff.[27] Rooney was captured at Gettysburg, and Rob, as an artillerist, was constantly in the heat of fire.[28] Custis could not divest himself of his desk job on Davis’s staff without offending His Excellency, but he did see battle during the retreat from Richmond, where he commanded an ad hoc division.[29] When Lee learned that his nephew Fitz Lee was hosting a ball in Charlottesville, he wrote: “There are too many Lees on the committee. I like all to be present at battles, but can excuse them at balls.”[30]

Following the devastation of the war, Lee worked diligently to recover not only his own fortunes, but those of his children as well, ensuring that his sons had homes and land to farm and his daughters were properly provided for, even though it cost him a large amount of what little was left of his own wealth.[31] He wrote to Rooney and advised him on how to make his land most productive.[32] He advised Rob on how to build his home and tend his crops.[33] At the end of the day when Lee returned home from his duties at Washington College, he would call for Mildred, saying: “Where is my little Miss Mildred? She is my light-bearer; the house is never dark if she is in it.”[34] During his last winter, that of 1869-1870, Lee amused himself and entertained Mrs. Lee and the children by reading aloud from the Iliad, the Odyssey, and the works of Shakespeare. In the twilight of his life, Lee traveled southward, hoping the warm climate would improve his health. Accompanied by Agnes, he determined to visit Florida so that he could visit his father’s grave. On the return trip, they stopped to visit Annie’s resting place in North Carolina. Throughout his travels, he was treated like a hero, though he could not fathom why. According to Agnes, he told her at the time: “Why should they care to see me? I am only a poor old Confederate.”[35]

Throughout all his trials, travails, and triumphs, Robert E. Lee was the man he taught his sons to be: humble, honest, diligent, brave, discerning, frugal, pious, loyal, and dutiful. As his greatest biographer pointed out, victory did not make him vain, nor fame make him proud, nor defeat make him bitter.[36] Doubtless Lee would have agreed with Rudyard Kipling when that poet wrote: “If you can meet with Triumph and Disaster, and treat those two impostors just the same… If you can fill the unforgiving minute with sixty seconds’ worth of distance run, yours is the Earth and everything that’s in it, and—which is more—you’ll be a Man, my son!”[37]

[1]Preston, Margaret J. “General Lee After the War.” The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine, 38 (May-Oct. 1889), 275-276.

[2]Freeman, Douglas Southall. R.E. Lee: A Biography, 4 Volumes (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1934), Volume I, 106. All R.E. Lee citations refer to the online transcription of the first edition which can be found for free at the following link: https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Gazetteer/People/Robert_E_Lee/FREREL/home.html

[3]https://www.nps.gov/arho/learn/historyculture/the-lee-family.htm

[4]Preston, “Lee After the War,” Century Illustrated, 274.

[5]Ibid., 276.

[6]Jones, J. William. Life and Letters of Robert Edward Lee, Soldier and Man (New York: The Neale Publishing Company, 1906), 145.

[7]Ibid.

[8]https://leefamilyarchive.org/reference/addresses/graves/01_index.html Of all the examples Lee could have given to Custis (Washington, Jefferson, figures from Scott’s novels and the classics), why on earth would the Virginian, Episcopalian Lee have praised a Puritan from Connecticut? Regardless of that, Custis denied the letter’s authenticity.

[9]Jones, Personal Reminiscences of Lee, 369, and Lee Jr., Robert E., Capt. Recollections and Letters of General Robert E. Lee (New York: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1904), 16.

[10]Lee Jr., Recollections and Letters, 16.

[11]Ibid.

[12]Preston, “Lee After the War,” Century Illustrated, 273.

[13]https://leefamilyarchive.org/reference/books/hamilton/06.html Custis is not named as the recipient, but given the language employed, the fact that Rooney is mentioned as being with his father and mother in the letter, Custis’s then-attendance at West Point, and the fact that Robert Jr. was only eight at the time, point to Custis being the recipient.

[14]Freeman, R.E. Lee, Volume I, 346. The General had himself been assigned to the Corps of Engineers when he graduated second in his class. See op. cit., 82.

[15]Freeman, R.E. Lee, Volume I, 330-331.

[16]Freeman, R.E. Lee, Volume I, 410, footnote 19.

[17]Jones, Personal Reminiscences of Lee, 381.

[18]Lee Jr., Recollections and Letters, 26.

[19]Lee Jr., Recollections and Letters, 112-113.

[20]Lee Jr., Recollections and Letters, 303.

[21]Lee Jr., Robert E., Capt. Recollections and Letters of General Robert E. Lee (New York: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1904), 15.

[22]Taylor, Walter H., Lt. Col. Four Years With General Lee (New York: Appleton, 1878), 76.

[23]Lee Jr., 79-80.

[24]Lee Jr., 80.

[25]Lee Jr., 81.

[26]Ibid.

[27]Lee Jr., Recollections and Letters, 119-120. Historians may have cause to lament this last act of restraint; Lee the Younger had an excellent memory, a fine sense of humour, and an admirable command of the pen. Had he spent more time with Lee the Elder during the war, a great many details now lost to time might be known to us.

[28]Crocker, H.W. Lee on Leadership, 126, Freeman, R.E. Lee, Volume II, 396-398, Lee Jr., Recollections and Letters, 76-77.

[29]Freeman, R.E. Lee, Volume IV, 63, 70-73.

[30]Lee Jr., Recollections and Letters, 121.

[31]Freeman, R.E. Lee, Volume IV., 379-394.

[32]Lee Jr., Recollections and Letters., 326-329.

[33]Lee Jr., Recollections and Letters., 241-244.

[34]Preston, “Lee After the War,” Century Illustrated, 276.

[35]Preston, “Lee After the War,” Century Illustrated, 276. For a fuller account of the journey and visits, see Lee Jr., Recollections and Letters, 376-430, and Freeman, R.E. Lee, Volume IV., 433-467.

[36]Freeman, R.E, Lee Volume IV, 503.