By Bulelani Jili, EPIC Scholar-in-Residence

Many of China’s tech firms are now among the largest companies in the world. They offer numerous surveillance products initially designed for domestic use but now exported globally. The rise of China’s surveillance tech infrastructure has inspired much scrutiny of China’s behavior, research into potential consequences for domestic and international politics, and questions about the degree to which China is promoting invasive surveillance practices abroad. The heightened scrutiny centers around the increasing collaboration between government actors in Beijing and private Chinese actors in the sale of surveillance tools. Concerns are further amplified by the fact that China and its large firms are increasingly seeking to change the norms and standards for the global use of digital surveillance technologies.

Cyber sovereignty

Beijing’s ambitions to shape the global governance of cyberspace is organized around the notion of cyber sovereignty or “wangluo zhuquan”. Simply put, China wants individual countries to have the right to choose their own internet development and management. This entails recognizing the country’s right to engender and employ its own public policies about cyberspace and, by extension, online free speech and privacy. Under cyber sovereignty, countries would discourage cyber hegemony and avoid interfering in the internal affairs of other states. When China’s notion of cyber sovereignty is contrasted against the U.S. government’s position on cyberspace, there is a clear conflict. While the U.S. and its allies advocate for a more open, free, and multistakeholder approach, which provides open platforms for private actors and civil society organizations, China wishes to promote a complete counterapproach that asserts the interests of the government over non-state actors. This state privilege is about reining in the supposed excesses of cyberspace that Beijing considers a threat to political and social stability.

For Beijing, research and development investment in surveillance technologies supports both the ambitions of the party-state in acting as a global technology leader and enhancing the means of domestic social control. Maintaining social stability, or simply the absence of social unrest that undercuts party authority, has been the primary policy goal for decades. In an early example of pursuing this goal, the State Council approved plans to develop a national information system in 1990. This included the Golden Shield Project. Proposed by the Ministry of Public Security, the chief purpose of the program was to establish a national CCTV network that would digitize the public security sector and thereby scale the means of state security and the growing demand to control data.

Greg Walton’s critical study explores the early developments of this initiative. He precisely illustrates how the program from the founding aimed to integrate an online database with an all-encompassing surveillance network. Crucially, the report reveals how technology developed in Canada and America is procured and utilized by Chinese state authorities. Oracle has recently sold its software to Liaoning police, which allows law enforcement the means to better track and identify potential suspects. Oracles’ data security service was also being used by other Chinese security services, including Xinjiang police.

Safe City

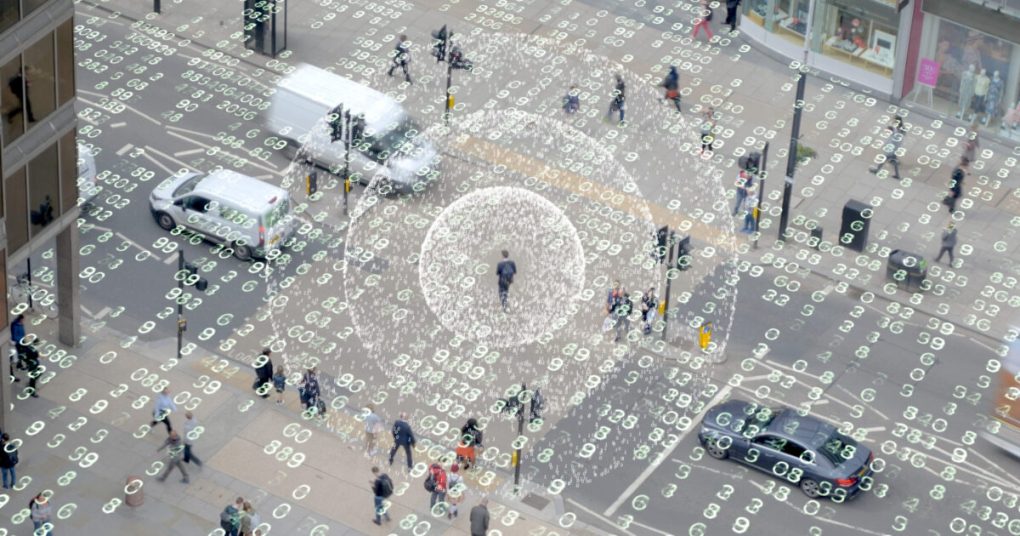

The safe city model is an evolution of the Golden Shield Project. More precisely, it is a computational model of urban planning, which promises to optimize operational efficiency by leveraging information and communication Technology (ICT) systems. Like the smart city, it is a product offered by Huawei in China but also sold across Africa. The safe city integrates data from multiple sources, including retail stores, banks, utility companies, and biometric data from facial recognition cameras. The centralized information systems processing this data are referred to as city brains. These endeavors bring together civilian-commercial industries with the state to enable multi-area surveillance. Underlying the turn towards data-driven governance (a term used to describe this form of surveillance) is Beijing’s belief in scientific development (“kexue fazhan”), which presumes that societal challenges like crime can be numerically expressed and resolved through technical interventions. This emphasis on innovation and the fetish for digital solutions arises from a presumption that the reduction of crime merely relies on the application of technology rather than improved social conditions. In other words, complex social processes like crime are inferred to be, and reduced to, purely technical matters without long structural histories.

Private-Public collaboration

Public-private partnerships have propelled the emergence of China’s digital surveillance efforts, which allows for abuses such as monitoring ethnic minority groups in Xinjiang. Hence, digital tools allow the Chinese government the means to conduct ubiquitous surveillance operations on anyone perceived to be a threat to social stability or undermine the values of the CCP.

Given the business incentives for developing a relationship with the state, companies arguably have little to no reasons to decline work from the government, even as they claim ignorance about the details and consequences for that work.

In addition to realizing the ambitions of cyber power at home, China’s drive for tech leadership extends beyond its borders. The tech firms that make its cyber capabilities possible are both small cyber research start-ups and leading global tech firms. Researchers have found that about 63 countries have Chinese sourced AI surveillance technologies. The technologies that were developed for the Golden Shield Project are now being exported across the globe. Selling digital surveillance and cyber capability technologies, supposedly for state security purposes, is not unique to China. Western corporate actors and others are also involved in the mass sale of surveillance and cyber capability technologies. What makes Beijing distinct from other exporters is the political and legal system that these technologies come from and, more crucially, how the party-state promotes their use in the Global South.

Multilateral Institutions

Beijing utilizes platforms like the BRICS, Belt and Road Initiative, and the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) to endorse the export and use of surveillance technologies. For instance, through FOCAC and the China-Africa Defense Forum, China has signed resolutions to increase cooperation in areas like counter-terrorism, cybersecurity, and safe city initiatives. This promise is also supplemented by commitments to provide training, finance, and technical assistance to governments on topics ranging from cybersecurity to digital forensic techniques.

In South Africa, the increase in use of Chinese digital surveillance tools comes along with police-to-police cooperation and training. In 2017, a delegation of South African parliamentarians traveled to Shanghai to tour Shanghai’s Public Security Bureau’s 24-hour command center to further study the city’s digital surveillance system. This is tied with China’s strategy to promote and legitimatize its conception of cyber sovereignty. Beijing’s effort to set norms and standards for cybersecurity garners legitimacy in part from its contributions to development and cyber capacity building in the Global South.

Proportional Accounts Although individual African countries procuring Chinese technology have their own local interests, the party-state’s active push to support the export of domestic surveillance tools also shapes outcomes. Drawing attention to how the party-state leverages demand for its own geopolitical interests does not downplay African state agency and their ability to detect outcomes. Rather, it asks us to consider proportional accounts and frameworks that demonstrate the degree to which African efforts are shaping these unfolding relations while also understanding the interplay between Chinese tech providers, African actors, and the party-state ambitions to promote its vision of cyber sovereignty. This layered approach seeks to expand our understanding and forestalls the potential long-term impact of China’s growing cyber power on the global stage.

AUTHOR

Bulelani Jili is a Ph.D. candidate at Harvard University, where he is a Meta Research Ph.D. Fellow. He is also a Visiting Fellow at Yale Law School, a Cybersecurity Fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School, a Fellow at the Atlantic Council, Research Associate at Oxford University, and Scholar-in-residence at the Electronic Privacy Information Center. He will be writing a series of blogs on Chinese surveillance tools in Africa.