June 02, 2023

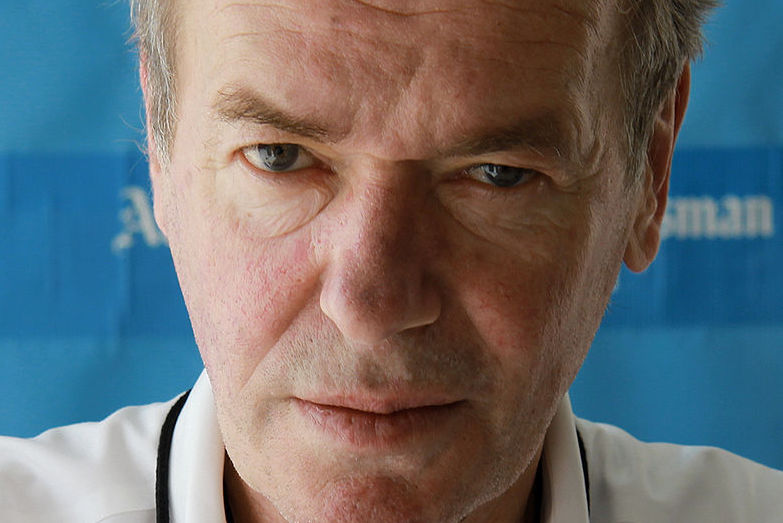

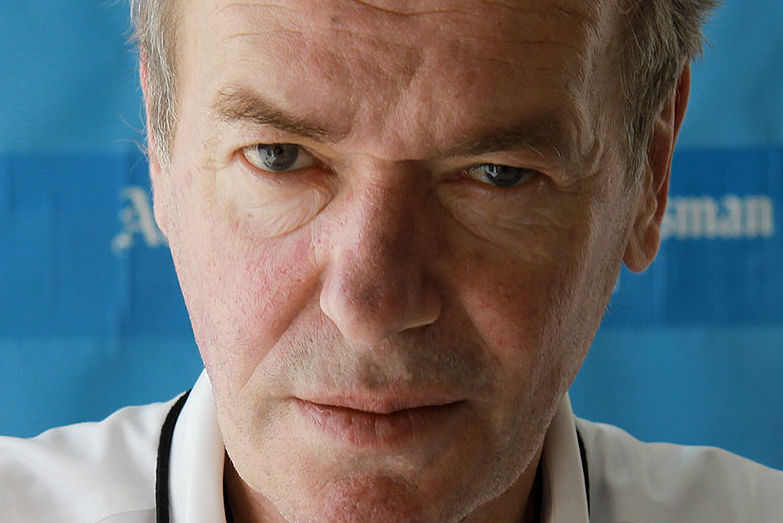

Martin Amis Source: Larry D. Moore When I learned that Martin Amis, the author, had passed away, I felt a stab of grief. I did not understand him personally, and heard him speak just when, at the funeral for an acquaintance of mine. He spoke well, however it was not an occasion for rhetorical sparkle. He behaved like a perfectly civilized male, and in a dignified and modest way.

Part of the factor for my sadness was that Amis was only six weeks older than I, and therefore his death brought house to me by how thin a thread my own life is now suspended. He died of cancer of the esophagus, like his good friend, the reporter Christopher Hitchens, and this is not an illness from which an easeful death is to be anticipated. Possibly it is illogical to feel more for a complete stranger of one’s own age than for a stranger of a very different age, however man does not live by logic alone.

I had read a few of Amis’ books, however little remains in my mind of them except for their environment, which I discovered uncongenial. In some cases I believed that his writing was cleverness in search of a topic. In an interview in The Paris Evaluation, he said that he had observed that individuals who lined up for signed copies of his books tended to be what he called sleazeballs, in contradistinction to the lines for finalizings by other authors. The word he picked to describe his enthusiasts appeared to me a dreadful one, however I admit that, when it pertains to vocabulary, I am as chaste as a Victorian maiden. Such words (other than in reported speech) bring a blush to my cheek, half of embarrassment and half of disgust. I might list several others in common usage but will avoid doing so.

“When Martin Amis said that individuals who desired signed copies of his books were sleazeballs, I do not believe he was being self-critical, however rather self-congratulatory.”

The Guardian paper, reporting his death, which from my present viewpoint appeared untimely, said that Martin Amis was “an era-defining author,” however this appears to me to have something profoundly snobbish about it, in the exact same way that le tout Paris, taken to mean “everybody,” is snobbish. Amis was certainly not a national figure as was, state, Charles Dickens, and in any case nationwide figures do not necessarily “specify an age.” It is frequently the case that those who bestride the world like colossi– the literary world, that is– are forgotten ten years after their deaths, their giant reputations deflated to absolutely nothing, like pricked balloons. Often they undergo resuscitation years later, more frequently not. One has just to peruse the list of Nobel Prize winners to understand the fleetingness of much literary fame. Time will inform whether Amis will be read in fifty years’ time (though not by me, that much is particular); however if I had to wager, I would bet versus. Maybe this will be due to the fact that no one will be interested in the period he allegedly defined, or possibly it will be due to the fact that his work is not of enough interest, sub specie aeternitatis, to endure into another age. I might be incorrect.

Amis illustrated a loveless, solipsistic world in a satirical, and for that reason critical, way, however one thinks that he also wished to be part of it, which in any case he was so soaked up in and by that world that he could not imagine any other. Definitely, a return to the reasonably purchased world of his childhood (albeit that his dad played his part in producing its destruction) was not possible, anymore than one can remake fresh eggs from an omelet. The fairly ordered world of the very first half of the 1950s remained in some aspects less free than the terrible world of Martin Amis’ London books of the 1980s and ’90s, in which individual excess and its concomitant dissatisfactions were the norm.

Amis, I believe, loved what he disliked. This is not an emotional contradiction unknown to me, certainly I experienced it for much of my career. My topic was the social breakdown in Britain, a source of endless interest to me. Frequently I was uncertain whether I must collapse with laughter or rush approximately the roofing system to throw myself off. Who would not feel this odd and contradictory pair of impulses when told in all apparent seriousness, as I was, by a lady who was describing her most current horrible partner, “I’ve asked him not to strangle me in front of the children.” The absurdity of it is hilarious, however the social world to which it points is horrifying: one in which strangulation is taken as a normal part of relationships (she did not experience autoerotic asphyxia, that odd condition in which people, usually men, strangle themselves in order to increase the sexual arousal of their fantasies).

The fact is that the lower depths, which we feel ought not to exist, are constantly interesting, in the manner in which vice is always more intriguing than virtue. Authors find it a lot easier to portray bad guys and villainy than heroes and virtue, and are normally more successful at it. (One of the victories of Alexander McCall Smith’s Mma Ramotswe series of books, about the No. 1 Ladies’ Investigator Company, is that he has created an excellent heroine who is in fact intriguing.) Similarly, we can picture a thousand hells but not a single heaven.

Thus, our head tells us something, that the lower depths must not exist, however our heart informs us the opposite, that life would be the poorer without them.

I expect the problem develops when the lower depths predominate; that is to say, when much of society comes to resemble its previous lower depths, whose way of living is trendy instead of merely the things of prurient interest. When Martin Amis said that the people who wanted signed copies of his books were sleazeballs, or what may once have been called degenerates, I do not think he was being self-critical, however rather self-congratulatory. Sleazeballs had one fantastic virtue or benefit over those who stood in line for signed copies of, state, the books of Julian Barnes. The latter, according to Amis, were civilized, middle-class, informed professionals. Therefore, one may presume, Amis felt that they were artificial, not genuine; the sleazeballs, by contrast, were genuine. Hence, to be sincere is to be awful; but even I, in all my misanthropy, do not go so far.

Theodore Dalrymple’s most current book is Ramses: A Narrative, published by New English Evaluation.